Vol. I, Issue 2: DESPEDIDAS AND DISCOVERIES

In OÍSTE's second issue of 2023, Peace Corps volunteers share stories about unexpected quirks of service and more.

A note from the Editor-in-Chiefs:

When we signed up to be Peace Corps volunteers — in a different country with a different culture — we knew we were committing to two years of constant flux. Even with all the research in the world, there’s no way to prepare for a drastic life change. Thus, as many volunteers approach a year of living abroad, we asked contributors to consider all the unexpected quirks of service.

For the second issue of OÍSTE redux, volunteers share stories of hard goodbyes and decisions; navigating a foreign, food-based culture with diet restrictions; observations of exploitative child labor laws; indirectness; learning to love against better instincts; gender roles and machismo; race and xenophobia. This issue doesn’t offer answers or black-and-white solutions. Instead, it raises questions and prompts conversations, some easy, some uncomfortable. It also champions laughter and perseverance. This newsletter will cut off in your inbox so be sure to click on the title to read it in full on-site! (P.S., Sharebear, we all miss you dearly. P.P.S., Welcome to Colombia, CII-18!)

All Hail Sharon

Lorenzo Boni Beadle, Ron Deb, Soledad Garcia-King, LaTesha Harris, Boyacá, Colombia, CII-16

LORENZO: It feels good to write about someone you care about when you know, with confidence, that you’ve noticed something wonderful and concrete about them. This means you get to dig deep into online thesauruses and find the most well-tailored words of admiration where, normally, lower-resolution adjectives suffice — rather, you’re comfortable with low-resolution descriptors as you don’t know enough about the person to zip through the full lexicon of weird little signifiers. Either way, Sharon is perspicacious. She has perspicacity. She is filled with perspicaciousness.

This is what has solidified for me after dozens of “first times” with Sharon where she has contributed ideas, insight, or inspiration that seem to have been drawn from some kind of deep, preternatural instinct. I’ve always been on the lookout for concepts that gather disparate notions and piece them together in a sensible manner — those that help crystallize profound understandings of the world. Generally, these crystallizing concepts are not really about myself or other people I know, but instead have a broad, academic tenor and will probably never personally serve me. Sharon, on the other hand, offers crystallizing concepts for the self. This is remarkably difficult to achieve and extraordinarily valuable. It’s a gift whose offerings speak in how they help fortunate recipients and what they reveal about the giver. How much they notice. How much they care.

In a recent New York Times op-ed penned by Noam Chomsky and two colleagues, they write the following: “The human mind is a surprisingly efficient and even elegant system that operates with small amounts of information; it seeks not to infer brute correlations among data points but to create explanations.”

This description succinctly captures what is so mysterious and beautiful about how we navigate the world. We are graceful. And I’ve seen Sharon emblematize that in a profound and powerful way: the observations she makes, the advice she gives — they are crystals of grace.

I am so happy I met you, traveled with you, and learned from you. I know that you will crystallize so much for so many more.

RON: When I first met Sharon, I thought she was a boring administrative person from an United States charter school who had joined the Peace Corps. She came late and we had already figured out whom we got along best with in our cohort, so I would’ve been fine ignoring her for the rest of service. My opinion of her didn’t change until we started traveling together. She’s pretty cool, but high maintenance. Still, no matter what situation she’s thrown into, she’ll figure things out. She chooses the best places to stay and the best things to do without caring about the price tag. She always says that money comes back. One trip, I was in charge of booking and chose a hostel with a shared, public bathroom. Even though she hated it, she never told me so. My bank account will be happy now that she’s gone. Still, Sharon was one of the moms of my main travel group, so I do plan on visiting her in [REDACTED] despite being a cheap person.

SOLEDAD: The first time I met Sharon, I was relieved to no longer be the only Peace Corps Colombia volunteer not in their 20s. She struck me as friendly but distant. I guess she felt left out since we all knew each other already and didn’t know too much about her. However, I really got to know Sharon the first time we planned a “Yep, it's a road trip” adventure. I shared a room with her at the Tryp hotel, and one early morning, we had a cup of coffee together. We talked about our lives back in the States: our experiences as teachers, wives and mothers. From the beginning, we hit it off, but what really sealed the bond for me was an intimate conversation about caring for dying parents. I shared stories about caring for my father until his last breath and dealing with pandemic restrictions while I accompanied my mother through her passing. Sharon shared experiences about caring for her mother. This topic is foreign to the rest of our cohort. I shared these intimate details, cried a few tears, and confided in Sharon about my deepest feelings and concerns. From then on, Sharon has been my go-to person when I am feeling down, frustrated, or happy about something that has happened to me in Colombia. I will certainly miss her here, but I know I have made a friend for life that I can always go to when I need to talk.

LATESHA: The first time Sharon compared me to her Barbie clone of a daughter, I might have rolled my eyes. She, the definition of grace, did not begrudge me this hostility. In fact, she acknowledged the surreal concept. In her own words, she echoed my thoughts: Who was this white woman with a masterfully hidden Southern drawl and sharp eyes? And who did she think she was calling me a white girl? For a long time, I held a grudge born of a concern that I would become a surrogate daughter to be projected upon and never seen in full.

Obviously, I was an idiot. A mother's intuition is always right. I should've heard her and accepted the compliment. Because that’s what it was. Sharon goes out of her way to notice and uplift people; her compliments are never contrived. They never come with ulterior motives. During our initial meetings I failed to recognize that she held this quality, but I have since noticed on several occasions.

Once, after a long day of training, our little family attended Lorenzo’s book club in Tunja. Hungry and listless, we verged on irritation. Mine reached a point that I enlisted Sharon and Ron to leave with me before class ended. When we reunited again, Sharon pulled Lorenzo aside and told him he had done a great job at situating himself among his students because she could tell how much they trusted him. She couldn’t have known that, only hours before, Lorenzo had rattled off to me about how useless he felt as a teacher in that space. She validated him solely because she appreciated something and wanted to verbalize it. The next day, she offered loads of praise for Fabian — the heart and soul of our Pre-Service Training experience — regarding his facilitation skills and ability to energize a room. Sharon has, of course, given me endless compliments, many of them among the best I’ve ever received (admiration of my writing and my pink crop tops to start), but it feels trite to list them all here. To brag about one of her compliments is to lower its value. They are private trophies. Toward the end of a tour of Medellin’s Comuna 13 — which Sharon was 100% correct for booking even though I said we didn’t need it — Julio, our phenomenal tour guide, asked what we thought of it all. In a lapsed silence, she was the first to pipe up. “Good energy,” she offered absently. And then a downpour of compliments followed. She’s a champion of positivity, someone who believes in and distributes good whenever she can.

What I admire most about this practice of Sharon’s is that she does it when no one is around. She needs no audience to do the right thing. (I only know because I’m nosy and eavesdrop on private conversations.) She is a pillar of integrity. She sees people for their good and their bad and their everything in between. Imagine the person you hate most in this world, and I’m sure Sharon can identify their sacredness, can provide an example of something about them worth cherishing. Maybe I’m a bitter pessimist, but I consider that to be a beautifully rare quality in a person.

And the truth is, I am a lot like Sharon’s daughter who snuck out of the house to attend the The Formation World Tour when she was in high school. We both suffer from “the curse” as Mother calls it — the overwhelming understanding that everyone is dumber than us and, thus, wasting our time with their incompetence. We’re both strong-willed with strong opinions. We’re both writers with big dreams. When I offer my most biting remarks, Sharon will say, “Stacey would have said the same exact thing.” Still, as much as I resemble Stacey, I feel that I’ve become a second daughter to Sharon in my own right. When my blood boils, she lets me complain endlessly only to offer a brief, well-placed piece of advice that quiets my fire. I force the table to say grace, and she prays over me in return. She’s my newsletter’s most supportive reader and told me she would buy my books even though I’ve never told her what I want to write.

We’re both firm believers in treating people the way we want to be treated, so I learned how to compliment Sharon from Sharon. Wait and observe: find what is sacred to her (belief and family), and uplift her adherence to said values. Among the multitude of invaluable skills I learned from Sharon: how to hold on to tact and patience in the face of rage; firm self-advocacy; being an impactful educator. In a short year, she not only inspired me to be a better person but also showed me the path toward becoming one. I will miss her humor, her thirst for adventure, her generosity, her expensive taste, her wisdom, her honesty, and her shrewd analysis. (Sharon has never been wrong about a boy problem, and she doesn’t need more than ten minutes to come to the correct conclusion.) She’s a Queen amongst mortals, and I doubt Peace Corps Colombia will ever recover from losing her.

Sharon, we love you and we will miss you endlessly. You have a million opportunities to change the world once you get past your self doubt. Good luck in [REDACTED], and don’t forget this family when you inevitably find another one to roadtrip with.

Pantastic!

Savannah, Boyacá, Colombia, CII-16

I love to eat, and I hate to cook. In March 2022, during the medical clearance process of my application to serve in the Peace Corps, I was diagnosed with an auto-immune disorder called Hashimoto's Disease. To offer an extremely simplified explanation, Hashimoto’s is a disease in which the immune system attacks the thyroid when the body is under stress. The symptoms vary from person to person. I specifically suffer from hypothyroidism with typical symptoms being uncontrolled weight gain, hair loss, dry skin, and severe fatigue. Fortunately, my symptoms were deemed mild enough to avoid medication at the time of diagnosis. I had a month to design a way to manage my thyroid levels (THS, T4, T3, and TPO) through my diet while living in Colombia.

This has been the first time in my life that I haven’t had easy access to food I need. In the United States, eating was easy. I could go out or dine in on a frozen meal. However, here in Colombia, lack of access to ready-made meals — combined with my itty-bitty paycheck — has made cooking essential. After all, what makes more sense: buying one meal at a restaurant for 15,000 COP or buying a week's worth of fruits and vegetables for the same price? Here is the average food consumed on a daily basis in Boyacá:

Breakfast: maybe some eggs with rolls of bread or changua, a salty, milk-based soup with bread, eggs, and cilantro.

Lunch: the biggest meal of the day which consists of a slab of meat, huge mound of rice, and some type of vegetable assortment.

Dinner (with my host family at least): usually non-existent. However, if dinner happens, it consists of coffee and leftover bread from the morning.

While it took a few months to acclimate to the difference in meal portions, I struggled for a long time to find a diet that worked for my restrictions: No gluten, caffeine, alcohol, or eggs.

These restrictions have changed the way I live, function, and interact with others here in Colombia because general knowledge about gluten is widely lacking. Being a Peace Corps volunteer means week-long trainings where we stay at hotels and eat at hotel restaurants. Usually said restaurants serve a uniform meal to all staff and volunteers with exceptions for vegetarians, vegans, and myself. Unfortunately, I have never encountered a single restaurant staffer who knows what gluten is. I am frequently served plates devoid of rice, potatoes and plantain — all things I can eat. Most of the time — as restaurants do not serve substitution foods — this also means that I am served much less food than the other volunteers. I have no expectations that other people should memorize my dietary restrictions, but I feel like an asshole every time someone offers me bread, crackers, cake, etc. and I have to respond with: “Perdón, no puedo comer trigo.” In Boyacá, sharing food over a tinto is a large part of the social scene. You wouldn’t think turning down a coffee could ruin friendships, but here I am: friendless.

In my town, my dietary restrictions obliterate the three major food groups: bread, eggs, and tinto. I spent the initial three-month observation period starving as I exclusively ate fruit. I lost 20 pounds, feeling weak every time I adventured on my ten-minute commute to school. That was around the time that I found what would become MVP of my service: “Why Not” Gluten-Free Avena Pancake and Waffle Mix. I can only buy it in Tunja, a journey that requires an hour and a half of motion sickness along a bumpy road in an odd-smelling bus, but my GOD, as Gordon Ramsay would put it, “Finally some good fucking food.” Knowing I didn't have to stress about breakfast and start my day hungry renewed my will to try new things and recipes.

As I mentioned before, I hate to cook. Even more than that, I objectively suck at cooking. Throughout my cooking journey, 90% of all new recipes ended up burnt or inedible if I was not supervised. (My host mother has had to rescue more than one meal from my grasp.) This talent for disaster is precisely how I inadvertently invented my first pancake variation: scrambled pancakes.

You may wonder, “How did you get from Scrambled Pancakes to being Pancake God??!” The answer is simple; I had no other options! I could get good at making pancakes or I could eat fruit for every meal until summer 2024. After MUCH trial and error, I figured out the secret to making a good pancake: temperature. Then, I began to experiment with different flavors. I made pumpkin spice pancakes for Halloween, Strawberry Pancakes when I had too much leftover strawberry yogurt, Cinnamon Sugar Pancakes, Banana Pancakes, Double Chocolate Pancakes, and even Mugcakes when I was feeling lazy. I won’t lie, half of my motivation comes from the joy of finally being good at something in a place where I spend most of my time either messing something up or being totally lost in conversational Spanish.

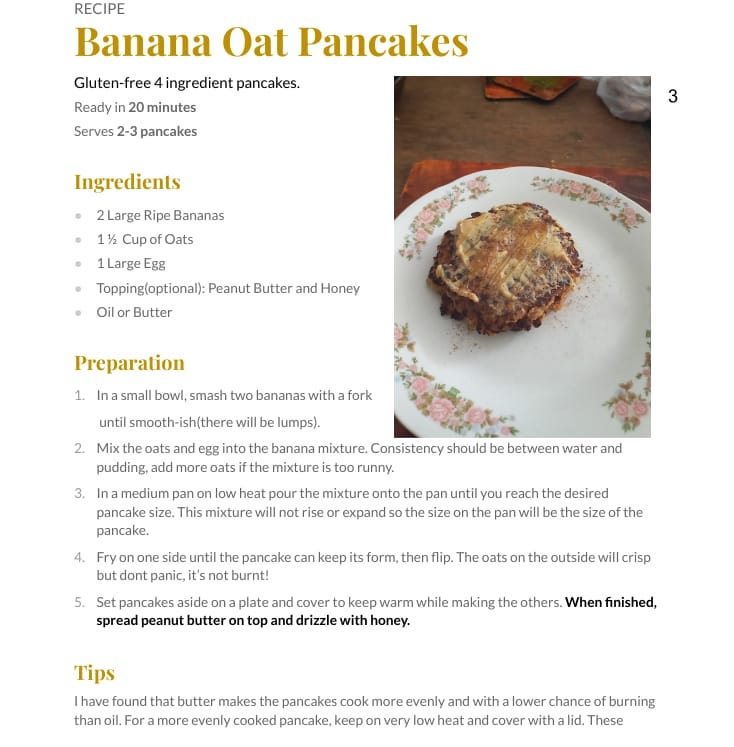

Thus, I will now bless you with my two favorite recipes: the most delicious being Cinnamon Apple and the easiest being Banana Oat.

The Cinnamon Apple Pancakes only exist because of a very cold vacation to Guasca where I and three other volunteers rented a cute AirBnB on a nature reserve. Before arriving, we split meal responsibility and I, believing there would be an oven, offered to make baked Oat Apples for breakfast. When we arrived, I discovered that the oven was an antique 100-year-old wood-burner that needed at least three hours to heat up and had no temperature control. Seeing my disappointment, one of the other volunteers offered to teach me how to make Breakfast Apples on the stove, a recipe with the same exact ingredients. Even though I didn’t do the best job making Breakfast Apples that time in Guasca, I was able to learn from that experience and make something yummy only a few months later. This recipe has the most steps, but it tastes the best and is connected to a happy memory.

Banana Oat Pancakes are something I had attempted to make a few times in the United States but perfected in Colombia with the help of another volunteer. I have spent a fair amount of time holding other volunteers hostage in our group chats, complaining about food or my lack thereof. Fortunately, our cohort has a few culinary-inclined individuals who offered some assistance. I adore this recipe because unlike the others it does not require a premade mix and all the ingredients are available in my town, therefore it is significantly cheaper to make.

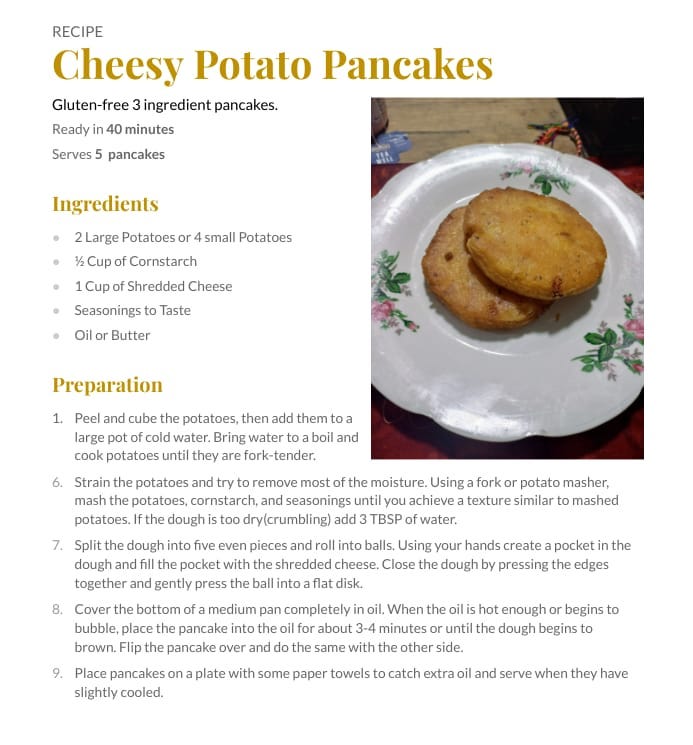

My previous host mom and I are very different people — culture, religion, world views, life experiences — but the one thing we were able to bond over was cooking. She had a lot to teach and I had a lot to learn. Therefore, I cannot take much credit for this recipe as it is a variation of a TikTok recipe that reminded me of arepas she taught me how to make. Those arepas are made with a masa of cornmeal, sugar, and water and with the same shredded cheese filling. (The similarities between the two recipes made this kitchen experiment the first my host mom actually liked.) I love all things spicy, so for my own cheesy potato pancakes I used a spice blend of salt, pepper, oregano, paprika, Red Robin Fry seasoning, and cayenne pepper — but any seasoning combination will work since the dough is so plain. I used a mix of mozzarella and pepper jack cheese since those are what I had on hand, but if you want to make a sweet version of this recipe, I recommend using a mild white cheese like mozzarella or queso blanco. I believe the original recipe was based on Korean potato pancakes, so I'd call this a Korean-Colombian fusion.

The Llorona / Street Cat Paradox

Ezra Weber, Galapa, Atlántico, Colombia, CII-17

La Llorona. It’s a name commonly whispered around campfires or candlelight, a weapon brandished as an intimidation tactic to inspire obedience among children in Latin America. Even before Peace Corps service, I imagined her as a fiendish banshee with a warped face draped in a ratty shawl with long, clawing fingers who preyed on wandering children. These days, I’m no longer convinced she’s a myth. I’d even go as far as to say that I’ve heard her blood-curdling wails rippling in the dead of night: “Mijooo — Miiijjoooo.”1 In my delirious half-sleep, when her treacherous cries seem clearest, the moans morph into desperate yowls of bothersome street cats in heat.

Stifling Caribbean nights prohibit me from closing my window and in my street-facing bedroom, the after-hours squabbles of desperate feline lovers echo in a disruptive cat-cophony. Often, I find myself wanting to burst from beneath my sheets to bash in their brains and wring their necks. My kitchen features a large machete and a neighbor-be-good stick (as my host uncle calls it). They would both come in handy in my holy crusade for peaceful slumber.

But with one foot in the waking world and another miles off in a magical dreamland, it’s impossible to distinguish the moans as cat-ish or human-ish (or, more specifically, as Llorona-ish). The worlds and the moans merge in the strange midnight hours, leaving me fearful of what lies beyond the three locks on the door and the cloves of garlic that I’ve begun to hang from my window. (I’m getting my folktales confused.)

Herein lies the troublesome paradox. Like Schrödinger’s cat — of course he used a damn cat — I know La Llorona is both out there and not as long as I remain hidden and indecisive. If I rise in the wee hours, thirsty for vengeance and cat blood, the scales of justice and reality will tip, and I’ll march straight into La Llorona’s clutches and be dragged off, never to be heard from again. As long as I stay behind my trusty padlocks, it’s nothing but a symphony of mangy cats defiling each other in a cultish orgy. Many nights I lie awake attempting to decode the mysterious howls as they bore into the side of my skull. I often try my shut-eyed best to block them out and fall asleep, but the cats continue to mock me as crafty old Llorona lurks in the shadows.

So, instead of being cocooned in a peaceful slumber, half of me lies paralyzed in fear — eyes bloodshot, mind racing — and my other half drifts down the Magdelena River, arm in arm with La Llorona on a raft made of buoyant cat bones. She’s actually quite a doll once you get to know her. I have learned that, just like the cats, all she really wants is a bit of company. The violence is just a façade.

Señorita Ally And Her Bandeja Paisa

Ally Robertson, San Estanislao de Kostka, Bolívar, Colombia, CII-17

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

You Can't Always Get What You Want

Renée Alexander, Ciénega, Boyacá, Colombia, CII-17

All I want is a cup of black coffee with some milk on the side. But, in Colombia, you can't always get what you want.

If you order café (coffee) in a café (cafetería), you'll get a cup of hot milk with a splash of coffee. If you ask for tinto, you'll get a small, plastic cup of black coffee — usually pre-sweetened — with no milk. If you ask for a café with leche al lado (milk on the side), you'll get a strange look because café already comes with leche, so why would you want more on the side?

Occasionally, if you are lucky, you can convince a waiter to bring you tinto puro (black coffee without sugar) with leche aparte (milk separate), but the milk will come in a second coffee cup, and it will spill all over the table when you try to pour some into your coffee. You will eventually learn to ask for a cucharita in addition to leche aparte which you can use to transfer small amounts of milk into your tinto and stir without making a mess. Still, you will get a strange look because why would you pour your own milk in your coffee when the waiter will do it for you?

After months being unable to get coffee the way I want it in Colombia — the third-largest producer of coffee and one of the world’s biggest consumers — I thought I had solved my dilemma when I heard Nira, Peace Corps Colombia’s training manager, order un tinto largo con un toque de leche (a tall black coffee with a touch of milk). I tried it myself in a café in Cartagena only for the waiter to tell me, "What you want is a macchiato."

I did not want a macchiato. I wanted a cup of black coffee with a little bit of milk. Even when I explained this, the waiter was very sure that a macchiato was what I actually wanted, because, even though it was a very small cup of coffee, the ratio of milk to tinto was correct in his opinion. Eventually, my friend and I convinced him to bring us cold-brewed black coffees — which he served in red wine glasses — with a few ice cubes. After he brought them, we asked for leche a parte y una cucharita. He gave us a strange look, but brought us milk in a coffee cup. He did not bring a spoon, so we asked again. Ten minutes later, he returned with a tray containing napkins and serving spoons. He painstakingly laid them out, first folding the thin paper napkins into tall triangles and carefully placing a spoon on each. This iced coffee was delightful. Still, it wasn't quite what I wanted.

Coffee is only one example of things that aren't quite the way I want them. In Colombia, pizza typically has no tomato sauce even when the menu clearly indicates a base of tomato. If a pizza does come with tomato sauce, that sauce might be ketchup, or, as they call it here, salsa de tomate. Pasta de tomate is a thick ketchup that is much sweeter than what comes in those tiny cans in the United States.

Generally, hamburgers are stacked high with toppings you don’t want. This can include ham, hot dogs, corn, potato sticks, an egg, or at least one of several sauce options that aren’t the defaults of mayonnaise and mustard. If you want a plain burger, you'll have to order the least offensive option — in terms of piles of extraneous ingredients — and individually list all the toppings you do not want. Still, despite your best efforts, you will forget to tell them to get rid of the cabello de angel because it is not listed as a topping on the menu because obviously all hamburgers and hot dogs are served this way. Occasionally, you will find a hamburguesa sencilla on the menu, and rejoice that you can order a simple hamburger without reciting a list of ingredients that really don't belong on a burger in the first place. Then, you will bite into your miracle burger and taste apricot jam. You may also realize that the burger is not made of ground beef because, in Colombia, a hamburguesa is just a sandwich on a round bun and can feature any kind of meat.

A complete list of things you’ll be hard-pressed to find in Colombia is much too long for a single article, but it includes the following:

a toilet seat or toilet paper in a public bathroom

a hand towel in any bathroom to dry your hands on

a steak you can chew enough to swallow

a steak knife

a sharp kitchen knife

a knife sharpener

an oven

a spoon that is not a large serving spoon

a hot shower with sufficient water pressure to rinse the shampoo out of your hair

regular (not diet) tonic water or ginger ale in a cocktail

a cocktail, at all, for that matter

a bus schedule

an accurate estimate of what time a meeting will start

a notification from the school when the day's class schedule has been changed

I know these sound like first world problems. They absolutely are. While they certainly cause frustration — particularly as they accumulate on a day-after-day basis — they are nothing but minor annoyances that Colombians don't even notice. Questions I often ask: "Why are the bathroom light switches located outside?"; "Why does the school schedule change on a nearly daily basis?"; "Why are washed dishes piled in a plastic basin, instead of in a dish drainer, or on a towel, where they won't sit in a pool of water?" Typically, the only response I receive is a shrug followed by: "Es a lo que estamos acostumbrados."

As a Peace Corps volunteer, my job is to get used to it too because I am here to integrate into Colombian culture. I am not here to challenge it.

Besides, there are many more elements of Colombian culture I would never want to change. The way my six-year-old host sister runs, screaming up the street, to leap into my arms with glee whenever I return home after an overnight trip. The way her nine-year-old brother patiently corrects my toddler-level Spanish without snark. The way Mono, the family dog, follows me to school and to restaurants and to fields with the sole purpose of barking at every other dog and human and motorcycle to warn that I am his person and they should keep their distance. The way fellow passengers go out of their way to help me when I need to ask the bus driver to drop me off at a TransMilenio station instead of Bogotá’s southern terminal. And the way a stranger digitally tracked me down via Facebook to tell me he had found my boyfriend's stolen passport on the side of the road. Better yet, the way he shipped it from Bogotá to Tunja after I declined his offer to hand-deliver it the next time he was visiting his family.

Yes: it is true that you can't always get what you want in Colombia. But, if you try, sometimes — and often even if you don't — you get what you need.

Circus

Lorenzo Boni Beadle, Cucaita, Boyacá, Colombia, CII-16

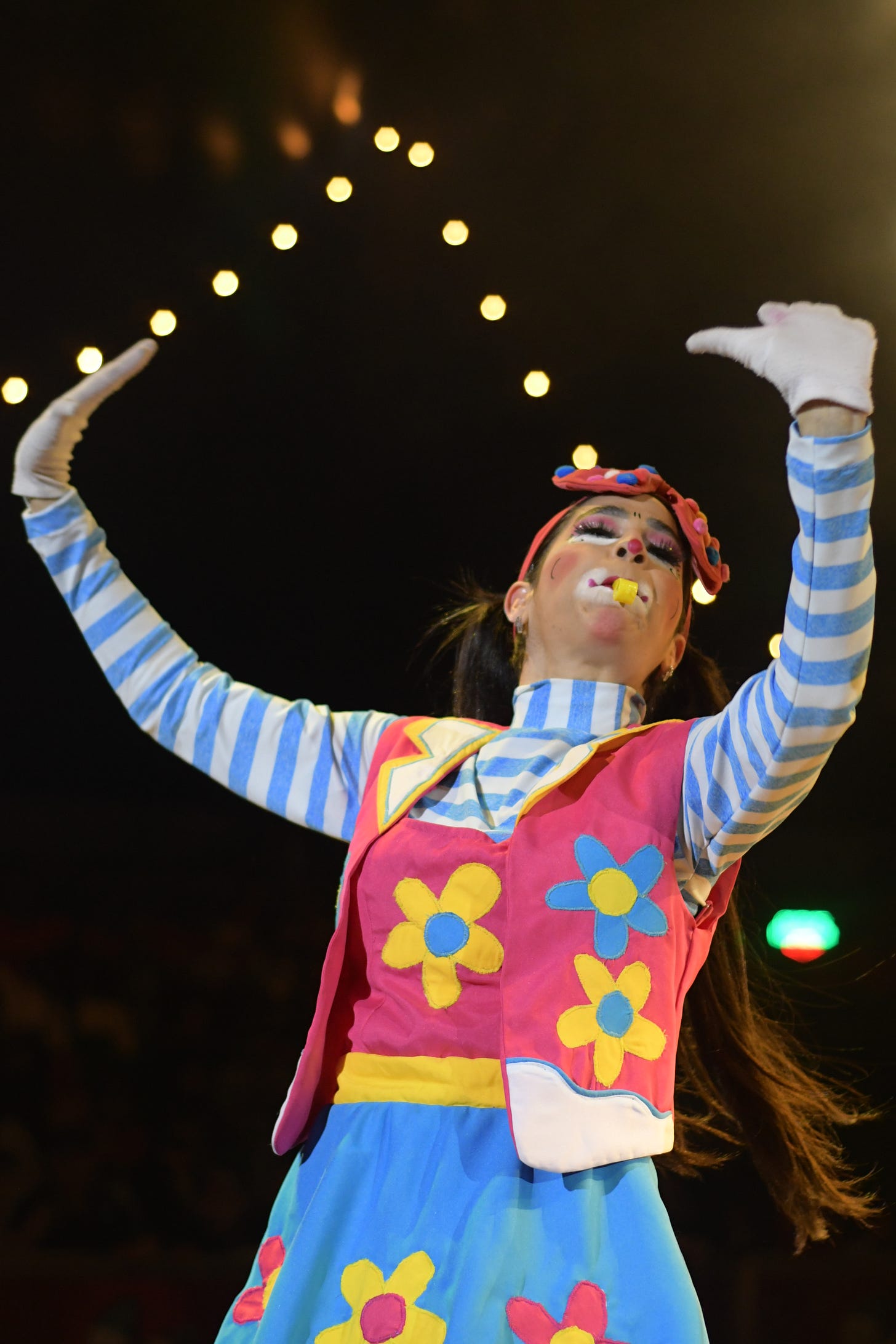

In keeping with the ephemeral circus thematic, CIRCO DE MEXICO DE LOS HERMANOS GASCA appeared seemingly overnight in an empty lot, a ten-minute walk from Peace Corps Colombia’s Tunja office. (I know nothing about the HERMANOS GASCA, so I’ve chosen to imagine them as venerable, wizened patriarchs of the ring who have engaged in the tumult of showmanship for the better part of 90 years.) As soon as I saw the newly-erected tents, I resolved to visit CIRCO DE MEXICO, but the voyage proved extraordinarily difficult to organize. We (the usual coterie composed of myself, LaTesha, Ron, and Soledad) finally managed to get together for the penultimate showing, our delay a blessing in disguise as tickets were half off. Thanks to my father’s circus hobbyism — a much more fascinating interest than I gave it credit when younger — I’ve been to more circuses than the average person. Therefore, I’m not going to say that CIRCO DE MEXICO brutally outstripped its North American competition, but I will say there are benefits to operating a circus in a country where the rule of law has not established as tight a stranglehold on entertainment as in the United States.

CIRCO DE MEXICO is frenetic. Everyone is tasked with multiple roles: a disguised, bumbling usher is the foil to a trickster clown in one act only to transform into the dashing HOMBRE BALA in the next where his svelte frame blasts out of a cannon and elicits universal audience applause. A 14-year old (we believe him the son of the ringmaster) is acrobat and clown and musician (specializing in playing a glass bottle xylophone while standing on his head) and — here, we arrive at the unique benefits of the Latin American circus — a participant in EL GLOBO DE LA MUERTE. When anonymous crew members dressed in black wheel out a spherical cage — the titular GLOBO — LaTesha screeches, “Oh my God, they’re gonna do Ryan Gosling from Place Beyond the Pines!” Indeed, they did do Ryan Gosling from Place Beyond the Pines, better known in the GASCAN dialect as EL GLOBO DE LA MUERTE. (To the man on the street: putting a bunch of motorcyclists inside of an immense, steel orb and forcing them to ride around its interior while inhaling grotesque volumes of exhaust.) I haven’t bothered to examine the relevant statutes, but I am confident that the American legal code would not sanction the participation of a 14-year old in EL GLOBO DE LA MUERTE.

The gaping depth of this lapse in judgment is evidenced as our natural-born star and ring protagonist strolls out in front of the audience — clownish attire traded for a dashing motorcyclist’s uniform — who receives him with thunderous excitement. Prior to his entrance, EL GLOBO DE LA MUERTE had hosted three simultaneous riders. He would be the fourth. His age enhances the thrill — the risk of catastrophic failure is ever-Damoclean — but he rides the cage with unwavering confidence. EL GLOBO DE LA MUERTE does not exceed the four-rider configuration, making our 14-year old hero the adrenal apex of an act that is already the circus' peak.

The other clowns are largely mediocre, and the high wire act was decent. There are some stylized gymnasts whose combination of balance, contortion, and phosphorescent leotards is delightful, and bizarre, to watch. Intermission features an extremely unsettling polar bear mascot whose white fur completely ruined the exposure of every (extortionately-priced) photo one was meant to take with him.

While I certainly would have liked to meet at least one of the titular HERMANOS GASCA, I was still able to interview a couple of artists and get a glimpse of the Latin American circus Weltanschauung. The first, Leonardo, explained the fairly liquid and international market for year-long performer contracts that brought him from Venezuela to countries all over the continent. (While he works in Colombia, Leonardo’s four brothers landed themselves circus work in Switzerland [two], London [another], and Chile [the last].) For CIRCO DE MEXICO, Leonardo alternates between acrobatics, shooting himself out of a cannon as an HOMBRE BALA, and participating in EL GLOBO DE LA MUERTE. At the labor law-violating age of six or seven, the now 26-year-old began his career with acrobatics before learning increasingly perilous arts. (He considers this a late start, especially when compared to those who were born in the circus to circus parents — an authentic performer’s lineage.)

Inez, Leonardo’s sister-in-law by way of one of his brothers in Switzerland, has been in the circus for seven years — first in concessions, then as a dancer, and now as a clown. She tells me that she hates constantly packing, and that while they once had to perform in the midst of a flash flood, she finds circus work more tranquil than alternatives. I learn from the two of them that inter-performer relations tend to be quite strong; while there are many circus talents across Latin America, there are relatively few specialized in certain acts (such as EL GLOBO DE LA MUERTE) so you are likely to encounter the same people often, even across countries. In addition to marital matters, this congenial environment aids performers in quickly becoming accustomed to new circuses.

As Leonardo leads me through the tents — where performers prepare for their final show in Tunja — we eventually encounter a woman teaching children. A volunteer, she represents the National Council for Educational Development (CONAFE), a Mexican agency that offers learning opportunities for marginalized children who have limited access to educational resources. Over children loudly competing for her attention, she explains that CIRCO DE MEXICO qualified for CONAFE’s assistance by being a firm operating abroad owned by and featuring Mexican nationals. After their lesson, the children were to practice gymnastics. Needless to say, being sent to a circus overseas is an unusual and difficult-to-foresee outcome of signing up to be a volunteer teacher.

Just as it came, CIRCO DE MEXICO DE LOS HERMANOS GASCA vanished, leaving me with an impregnable argument in favor of child labor and providing you an aimless essay whose sole purpose was to preface the wonderful photos taken by LaTesha and Soledad.

Life Lesson from Colombia: Reflections on my year as a Peace Corps Response Volunteer

Sharon Torkelson, Tenjo, Cundinamarca, Colombia, CII-16

Sharon is a Peace Corps Response volunteer who served for one year. At the time of publication, she will have completed her service and returned to the United States.

What is it that calls a person to leave what is familiar, what is safe, and what is home to experience life in another place? I am not sure how to define wanderlust, but whatever it is, it lives in me. American novelist John Steinbeck said it best: “People don’t take trips … trips take people.” In this vein, Colombia has stolen my heart.

As I complete the final weeks of my service, I realize the experience will forever change who I am. Living in Colombia has changed my perspective on how we, as Americans, receive people from other countries. It has renewed my hope for the next generation of leaders and changemakers. It has developed in me a new level of patience for completing the most basic of tasks like waiting for clothes to dry in the Andino region where it rains, off and on, several times a day; choosing between washing my hair or shaving my legs in a three-minute shower taken in varying degrees of scalding hot to freezing cold water; carefully washing, drying, and disinfecting a head of lettuce, leaf-by-leaf, to avoid getting sick on salad. Most of all, living in Colombia has taught me to appreciate the beauty of moving through life at a more reasonable pace, enjoying where I am and who I am with at any given moment while waiting to see where the day — or the bus — takes me.

A 2021 Gallup survey ranked Colombia as the “happiest country in the world.” Maybe it is because, unlike Americans, Colombians are not slaves to time. In Colombia, if you start your day with a “get-er-done” attitude — the to-do list, lots of expectations — you are setting yourself up for frustration by lunch time. Nothing ever goes as planned. When it rains, the roads are mud pits and it takes twice as long to get anywhere. Even on rare sunny days, many buses are standing room only and the drivers navigate pig-sized potholes, oncoming trucks, and rough mountain roads like Mario Andretti. Still, you rarely get where you’re going on time. Here, time is relative. Things start when everybody gets there. Power failures, water outages, and constant schedule changes mean the students for whom you endured a 30-minute bus adventure may or may not have class. I’ve learned to start my day with ideas and possibilities rather than expectations.

Learning to adjust my pace, both literally and figuratively, has helped me develop awareness and appreciation for some of the everyday images and sounds that punctuate my little corner of Colombia. When I am not traveling by bus, which has its own unique sensory images, I am walking the streets of my pueblo taking in its sights, sounds, and smells — the alluring aroma of sugar and yeast permeating morning air outside the panaderías, the persistent call of roosters at all hours of the day and night, the church bells welcoming people to worship in a massive cathedral whose doors are always open to all, and the endearing greeting of “Hola Profe” from people who recognize me as the gringa English teacher.

Walking is my primary means of transportation — to go to school or the library for my adult English class, to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables at the Saturday farmer’s market, or to stop by my favorite panadería and give into that aromatic temptation with a cup of tinto. Recently, I’ve found myself taking random walkabouts town just to hear the voices of excited students eager to practice their English as we pass in the street. Over the last year, we have progressed from “Hola Profe” to “Good morning, Teacher.”

One of the things I will miss most about Colombia is the notoriety of being recognized around town as Profe Sharon. At first, living among my students and running into them at every turn — at the gym, on the street, in the church and on the bus — was a little overwhelming, but it truly helped me integrate into the community. I am forever in awe of the teachers I support who do so much with so little. They welcome me into their classrooms with respect, patience, and the enthusiasm needed to try new teaching strategies even when they create chaos and disruption. And I will forever be grateful and indebted to my host family for welcoming me into their lives and into their homes without hesitation.

Colombians are easy to love, and perhaps it is because of the kindness and hospitality they extend to strangers. It is not easy to share your classroom or your home with a stranger, yet my dear friend and host, Luz, opened her home not only to me but also to my husband and adult children who came to visit. She taught me how to ride the bus and even rode with me on my first few times to make sure I knew how and when to get off. In Spanish, luz means “light” and my amiga Luz has lived up to her name as a guiding light for me throughout this past year.

It has been a memorable year. A challenging year. One of the best years of my life. The days were long, but the year was short. Expectations I had for my students, my teachers and myself when I arrived in Colombia no longer seem realistic. In fact, when I read the goals written during my first week in Tenjo, they’re laughable. Oh, to have the confidence and false hopes of a newly arrived English teacher in Colombia! One year later, I still struggle with Spanish conversational fluency. Most of my students are still speaking English at the novice level. Even though the teachers I support still teach English classes almost entirely in Spanish, some have changed their approach and are using some of the methods and strategies I suggested for their classes.

As I wrap up the final weeks at my site, the question that persists in my mind: Has my work here made a lasting impact? I would like to think so, but I am not sure I will ever know. Sometimes the footprints we leave behind provide a road map for the people with whom our lives intersect. Sometimes they simply create an easier path for people who follow. And sometimes they are simply erased and forgotten over time. No matter what I leave behind, Colombia has had a greater impact in shaping my path and my pace than I could have ever imagined.

The Gran Adventures of Arequipe and the Volunteer

Maida Walters, Tibaná, Boyacá, Colombia, C11-16

All Dogs Go to School

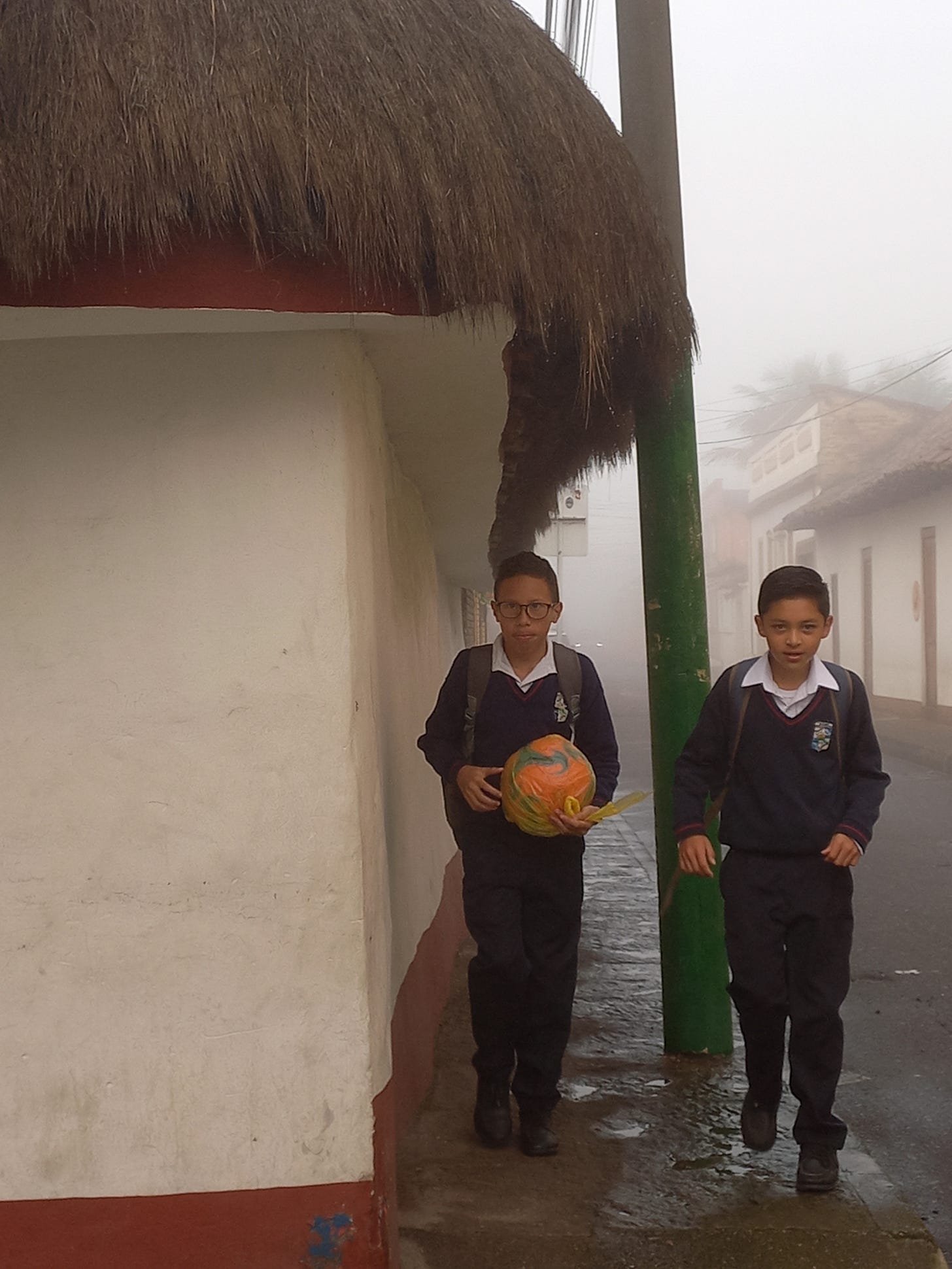

6:45 a.m., Boyacá, Colombia. Weekday. A flood of school children dressed in navy sweaters, plaid skirts, and dress pants pour toward the secondary school. Arequipe, up since dawn, pads between them. Trailing a group of school girls, she presses her nose into the knee-high socks of one of them. More often than not, she gets shooed. At worst, kicked. On occasion, thrown some leftover crackers or sweets.

The main gate of the colegio is a wide funnel for students and dogs alike. Occasionally the doorman gets a little too close with his stick, so she takes her secret entrance: a hole in the fence behind the main building. She skirts the building and slips into the shared teachers' room. And there — or sometimes in the main hall, perhaps on the secretary’s doormat — she waits.

It doesn’t take long. With a good morning to the profes, I walk into the teachers' room. Our daily greeting — mine and Arequipe's — consists of “you look beautiful today” and a fury of pets. Our meeting is cut short as I rush off to a classroom and Arequipe trots behind. The headliner of the show never arrives first.

Usually some English is taught. Hopefully some fun is had. Arequipe takes it all in from her corner of the classroom, sometimes drifting into a snooze when I’ve got class handled.

I use her name in an example of presenting people in third person: "This is Arequipe. She is valiant. She is not terrible." Her ears perk up at the compliment. She weaves between desks, checking in on student progress and receiving a few pats on the head.

When the bell rings, we head out of the class to a chorus of 40 students yelling bye-bye. We debrief with some more pets and head to the next class. That is our every day. We accept our respective identifiers as la perrita de Profe Maida and la humana de Arequipe.

The 2:00 p.m. bell rings, and I slowly walk home, weaving between groups of students. Arequipe does the same. At the door leading to my shared apartment, I give her a farewell and ask if I’ll see her later when I head out on errands. She wags her tail and lets me leave her. Tomorrow will be another day, and Arequipe will be expecting me.

Rolling in road kill and other pastimes

Arequipe, as with anything loved, should not be idolized. She inevitably has her faults, and the more I can learn to accept and perhaps even appreciate them, the less likely they are to bother me. Her most notable character flaw: hygiene. If there is something rank on the roadside, she will find it. Trash collection is the best day of the week. Susceptible stuffed garbage bags left on the street corners tempt her like candy scattered during a parade. Her odor has more than once prompted audible complaints from other profes. She harbors an army of fleas and intestinal worms.

So I have learned to love to clean her. I buy her flea medication which, disguised in a piece of sausage, she gobbles down enthusiastically. The school has a concrete sink that functions as her monthly bathtub. I hoist her up into the basin, proceed to lather her with anti-flea and tick shampoo, and pour bucket after bucket of water over her frame. Her brown eyes plead for me to let her go. It’s the only time she ever pulls her happy, flicking tail between her legs. After the first bath time — when she took off and rolled in the mud of the school’s garden — I learned to keep her on a rope until she dries.

She has taught me that if I can’t love her flaws, I can at least learn to accept them. I can’t foresee getting her to change her affinity for stench, so I can only change my reaction to it. And, after a while, really, one doesn’t mind the smell so much.

Fast times in the streets of Tibaná

The first run Arequipe joined me on happened to be an eight-mile out and back with sloping hills in the first half and the inevitable climb back up those hills in the second. Constantly, I worried that the distance was too far and she would get lost. Even when she charged ahead and looped back to keep me in sight, Arequipe’s tail never stopped wagging.

Since then, we’ve explored the veredas of Tibaná: hunting out the 19 rural primary schools that are hidden in the vast mountain slopes, searching out some new running routes, and steering clear of less than friendly guard dogs. Even though I’ve never encouraged her to come with me on a run, she has rarely left my side.

I’ve often thought that I can learn a lot from her trust: she has no idea how far or to where we might be adventuring. But she is always along for the run.

The lady and the volunteer

“La llamamos Arequipe,” said my roommate. The caramel-colored street dog was one of a few to whom Aleja routinely gave bread. Skinny and flea-bitten, the newly-named Arequipe wasn’t a looker. But, dumbfounded and overwhelmed in my first week at site, neither was I.

Initially, I kept my distance. I called her by name and patted her head. I chipped in to buy bread for her and the other street dogs. I talked with the neighbor to split the cost of having her sterilized when we both noticed her hidden under a car surrounded by a pack of macho dogs. But, and I was very clear on this, she wasn’t my dog.

I hadn’t wanted to grow close to any animal. I’d seen first-hand how treating a pet like a family member was a luxury in many places and a liability in others. Dogs were a form of insurance. A way of protecting property like a barbed wire fence or steel gate. Or they were pests — perros callejeros — that begged for scraps, chased motos down the streets, and slept curled like snail shells on sidewalks, fending off the cold. In my previous Peace Corps post, half a world and pandemic away, there was a dog who sat on my feet while I felt overwhelmingly lost and hungry and sad. Food scarcity prevented me from fully feeding myself, much less a dog, but she spent time with me without any more encouragement than a few pets. A small connection between two tired souls. One day, she hunted and killed a few chickens. I watched her be shot and die in front of me. I didn’t need to relive growing attached to something you can’t promise to keep safe.

Still, Arequipe, however perceptive and empathetic, wasn’t about to be told no. She played the long game of winning me over — first by following me on afternoon walks and then later to school. The students rolled with laughter as she strutted into all the classes right after me. The question: “¿Profe Maida, es su perrita?” I didn’t initially answer. But soon the question was replaced with a statement: “Profe Maida, es su perrita.” Lunch times, afternoon runs, waiting for me at the bottom of the stairs with her beautiful caramel color and bright eyes. It was the first lesson of many I learned from Arequipe: We can’t always control who we love, and we can’t always control when they’ll walk into or out of our lives. But we can control whether we show our love during the time we spend together. So she became mine, as she had obviously already decided I was hers.

A Gender Studies Concentration Proves Useful During Carnaval

Nyna Hess, Plato, Magdalena, Colombia, CII-17

Before Carnaval even started, I knew I wanted to go to the Burial of Joselito. I had to see this parade of people crying over a life-sized doll. Upon arriving, I was floored to see not only women dressed in black, wailing in mourning, but men in dresses, stockings, and oversized pearl necklaces. It was the closest thing I had seen to my favorite TV show, RuPaul’s Drag Race, since arriving in Colombia. My reverie ended when my friend wondered aloud why men were dressed as women in a country saturated en una cultura machista. While witnessing a man in a wig, dress, and gaudy red lipstick feign picking up a coin so that he could rub up against my friend was very amusing, it was also extremely disorienting.

After the parade, I sought understanding from my host family. They explained that Joselito, the life-sized doll everyone mourns, represents the life of the party. When Joselito dies on the last day of Carnaval, so does the celebration. When I asked about the men dressed in women’s attire, I was met with lots of shrugged shoulders. They passed it off as another triviality of Carnaval.

In most spaces on the coast during the other 361 days of the year, gender roles are strictly enforced and homosexuality operates within a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. Still, throughout the seven months I’ve lived here, homophobia has been casual and constant. I hear marica — an offensive homophobic slur in most Latin American countries, especially Mexico — incessantly. In coastal vernacular, it might be the most versatile grosería: it can be used after accidentally dropping something or to emphasize that your friend’s jeans look fabulous on them. And, of course, it can be used to castigate a boy or a man who is acting outside of his assigned gender roles.

Here, it is incredibly easy for people to discuss the language they use to divide themselves from the LGBTQIA+ community. A 23-year-old acquaintance explained to me that it’s totally fine to say this word, but she refrains from saying it if she knows she’s around someone she knows is gay. Once, during English conversation practice with a teacher, we started talking about the difference between “weird” and “strange.” The first example he gave is that "tipo raro" signals a gay man. It’s more serious for my counterpart: on more than one occasion, she has told me that a student’s gay family member is exerting an evil influence on them in her never-ending commentary on our students and their difficult home situations. It’s challenging to bite my tongue in these situations, to refrain from protesting that I myself and so many people I love are not evil or strange. But time and time again, I walk away from these conversations wishing I had said something instead of just looking uncomfortable.

Throughout multiple training sessions, I’ve been a broken record, asking for resources in these awkward conversations or how we can support students who come out to us. My desire to be assuaged in this area doesn’t come from wanting to say the right thing but rather to understand. I am searching for clarity on the cultural factors that have made it hard for my friend in a six-year relationship to admit to his parents that his best friend is actually his partner.

During In-Service Training, my project manager handed me a book and said it might provide the context I’ve been missing. It was Silvana Paternostro’s In the Land of God and Men: A Latin Woman’s Journey. Born and raised in Barranquilla to a wealthy family, Paternostro attended high school and university in the United States. As a long-form journalist, her research primarily focused on answering the question of why loyal, married women in Latin America contracted AIDS at such a high rate during the 1990s. The short answer: their husbands had extramarital sex. The long answer: they were sexually active with members of gay and transgender communities where there was more frequent transmission of HIV. Paternostro writes that in Latin America it’s an open secret that men having sex with other men is customary. As an explanation: When ideas of machismo are followed to their logical extent, the ideal man is so manly that he sexually dominates other men.

While reading, I felt excitement similar to the one I felt during Gender Studies classes where we unpacked academic explanations and learned vocabulary behind misogynistic systems. But this wasn’t theory or postulation; there were statistical trends and mountains of anecdotal evidence to support Paternostro’s claim that women, as well as members of LGBTQIA+ communities, were dying because of patriarchal ideas about sexual behavior. Reading this information in a context removed from the United States’ AIDS epidemic, I realized that homosexual attraction is a fact of human nature with varying cultural interpretations. Even though the men Paternostro writes about weren’t identifying as gay, they were acting on desires in a way that women and queer individuals couldn’t because patriarchal privileges let men dictate their own rules.

I return to consider Carnaval. What should I think? In a way — now that I know that the difference is the cultural interpretation, not the behavior — the new information is validating. It doesn’t realistically solve any problems, but it’s now easier for me to separate the perpetrator from the confusing act or message — to visualize the insidious patriarchal system behind these individuals — and to know that all around the world we are fighting the same beast with different faces.

Those men twerking in bodycon dresses and wigs: Is it a mockery of women and transgender individuals? An expression of repressed desires? To be honest, I’m not interested in interpreting it anymore. The pattern of men doing what they want and leaving marginalized groups to deal with the consequences is nothing if not predictable. Still, I should cut myself some slack. I didn't take enough 400-level courses to be able to identify the intersection of sexual behavior with gender politics in real time while trying to adjust to a new culture. At the very least, I hope it would make my professors smile to know that in the middle of the biggest party in Colombia, I was thinking about gender inequality.

Series of Unfortunate Events

Molly Devine, Campo de la Cruz, Atlántico, Colombia, CII-17

Molly is a Peace Corps Colombia volunteer who began her service in Boyacá and has since been relocated to Atlántico.

One

On site announcement day, I was hoping for a town in the Andes while most of my friends hoped for the Coast. I figured all of them couldn't stay on the Coast — some had to be placed in the mountains. Wrong. I opened my folder to see a small, rural, Andean village — urban population of 1,000 — located countless miles away from every one of my friends who had received coastal sites. I was excited for a change at first. However, as the days to site departure inched closer, I began to think I’d made a mistake pushing so hard for the mountains. This is when the first unfortunate event occurred.

Four days before site departure, I received a positive COVID-19 test result which meant I would not be able to bid a final farewell to my friends at our swearing-in ceremony. In Barranquilla, I sat in the volunteers’ lounge and quietly cried into my mask as staff members scrambled to find me a place to stay.

I spent the following days alone with my thoughts in a dark, windowless hotel room. I watched my swearing-in ceremony on Instagram live while awaiting travel logistics from the Peace Corps. When I finally received word that I could relocate to the Andes I boarded my flight with a sense of apprehension and forced positivity. “Well, Molly,” I thought, “it really can't get much worse than this.”

Two

When I arrived in Bogotá, some nice men helped me with my bags and then asked why I looked so sad. I had cried through the whole flight. A Peace Corps driver picked me up and took me straight to Tunja for the host family orientation session. When our Andean security officer glanced at me, he posed the query: “Altitude sickness?” I responded in agreement, “Yes, something like that.” I became an official Peace Corps volunteer when our Country Director presented me with my certification of Pre-Service Training completion.

En route to site, my well-meaning host mother voiced reservations about me living and working alone at my colegio as a young woman. Upon receiving my profile, she had relayed these apprehensions to Peace Corps Colombia staff. To start, my site has some of the highest alcohol consumption per capita in the country. My host mom explained that men start and end their days drinking in the almacenes with a mid-day break to work on their farms. The first time I sat with her in the almacén where she works, I was grabbed by multiple men. The Pokers clouded their judgments, so I let it slide. From there, it only escalated. When I walked by corners with certain almacenes, the men would call at me and invite me to join them. If I ignored them, they would walk toward me until I acknowledged their invitation. Not wanting to come off as abrasive because I was still new in the community, I would politely decline their offers and continue. Easier said than done. Quickly, I learned what corners to avoid, which resulted in me taking weird roundabout ways to get places in my four-block town.

Already grappling with homesickness, this additional burden compounded my fears. I was down so bad that I couldn’t even find solace in Taylor Swift and found myself playing Bad Bunny’s “Amorfoda” on repeat. I was isolated on a mountain and constantly dealing with sexual harassment. Nonetheless, I woke up every day, brewed tea, and headed to school to stay busy. The teachers were my saviors. Every weekend, they would collect me from my site and take me to different places in Boyacá. They would prepare meals for me and introduce me to their families and help me learn French. I had created a routine: one weekend in my pueblo and one away. I would count down the days until my weekends out of site.

I use journaling as a measure of how well I am doing. For the first month, I could not. I was running on autopilot, my body permanently in survival mode and all my emotions off. I would keep in touch with my fellow volunteers and see their amazing sites with great schools and homes, and compare them to myself — no fridge and virtually no population to boot.

During all this, my host siblings’ father unexpectedly moved in. He bought a flat-screen television, a fridge, and a new stove. He also paid for the construction of a brand-new front gate. Before I knew it, the inside of my house was being demolished. I packed enough clothes to last a night. Then, I headed to Tunja to meet with our security officer who decided I had to stay there until the completion of construction. Now, for the unforeseeable future, I had a daily commute: I woke up at 5 a.m. to catch a 6 a.m. bus that would get me to school by 7:15 a.m.. “I know I said this last time,” I told myself, once again alone in Tunja, “but now it really can't get worse.”

Three

One week into my exile, I planned to have lunch at a ramen restaurant on a quiet Sunday afternoon. Afterward, I planned to stop by the mall and grab snacks before returning to the hotel. I was wandering around UTPC, admiring the mountains and letting my mind drift. As I approached the monastery, a man crossed the road and pulled a knife out. This was absolutely his first rodeo because he took my phone and tote bag and asked if I had anything else — I did, but said no — before running down an alleyway. Some people who had seen the whole thing called the police for me.

The police officers took me in their cop car to do rounds. Afterward, they nicely dropped me off at my hotel, but not before asking if I had a boyfriend. And if I didn’t have a boyfriend, was it because I didn’t like Colombian men? “This is rock bottom,” I thought, numb in my hotel room,” things can only go up from here.”

Four

When I finished my two-week sentence in Tunja, I was eager to return home even if it was not a stable place. As if on cue, my host mom told me she had to go to Huila to visit her sick father whom she hadn't seen in years. In her absence, the father of her children would stay with us and care for the house. Once again, I was sent to the hotel and had to commute to my town and back to Tunja daily. At this point, the only thing I survived on was the promise of reuniting with my friends on the coast during Carnaval.

Five

One afternoon, after Carnaval, I decided to go to the river running through my site to read and reflect. I frequent this river, and always ensure that no one watches me turn off the road into the woods, but this time I was careless. A man followed me. He watched me for a few minutes. When he started to approach me, I called our security officer and dashed out of the woods. I reached the main road, and the security officer asked if I wanted him to call the police. I panicked because one of the police officers had been texting my mom about how he was interested in dating me.

When I admitted this concern, our security officer told me I could ask for a site change. That night, I slept on it. The next day, I packed up a weekend bag and got on the bus to Tunja. As soon as I met with our security officer, I broke down.

The rest of the afternoon was filled with calls with PCMOs and administrative staff trying to figure out what I could do. Luckily enough, some staff members were about to embark on a three-day road trip, visiting sites around Boyacá and offered to take me along. As we drove, staff told me that site changes are common in the Peace Corps but never easy. Our adventure ended in my small pueblo where I had an hour and a half to pack my life up into three bags. Again, I found myself in the hotel.

Staff let me know that there wasn’t a single site available for me, not in the mountains nor on the coast. I waited for two weeks, a 50% chance that I’d stay and a 50% chance that I would leave. On the last day of In-Service Training, they informed me that I would return to the coast and serve in a pueblo called Campo de la Cruz.

I’m here now, writing from my new host family’s home where I arrived two days ago. Last night, I finally began to process all the unfortunate events of the past three months and had a moment where I felt I could finally breathe. I’ve exited autopilot and survival mode. Although I know there will be many struggles to face in the future at my new site, I have an overwhelming sentiment of hope.

Finding My Venezuelan and Mexican Roots in Colombia

Ron Deb, Toca, Boyacá, Colombia, CII-16

Having spent my entire life living in the suburbs of Connecticut — where my most frequent exposure to Latino food was Moe’s — it’s been tough connecting to my Venezuelan-Mexican heritage.

Soledad, a fellow Mexican who grew up far more connected to her Latina roots but is routinely mistaken as Colombiana, shares my desire for good food. During a trip to Tabio, we stumbled across a Mexican restaurant that actually seemed viable. With our token white friends, Lorenzo and Sharon, we entered, hesitant because Mexican food in Colombia is more often than not bland sausage and unmelted cheese with heatless jalapeños thrown on top. To the average Colombian, the slightest degree of spice is a danger porque les produce gastritis. Therefore, the owner — a Colombian who had been trained by a Mexican chef — was thrilled by mine and Soledad’s ability to enjoy the spicy-by-Colombian-standards salsa. Both the owner and waitress kept bringing salsas with incremental amounts of spice. Soledad and I had no problem, a fact that inspired shock and excitement. Eventually, the waitress brought us the spiciest one they had. When Soledad reached for the bottle, the waitress rebuked her and said, “No, es para el señor,” before placing the salsa in front of me. It was only mild.

Members of my host family are somewhat frustrated by me constantly buying hot sauces and having my family fly bottles down when they come to visit. They compare my love for spicy food to that of a Mexican. When I eat with Colombian friends, they make sure to break out the rarely-used hot sauce. Staff at restaurants and other customers will sometimes stare at me in shock as I pile on hot sauce that is mild for my taste buds. I routinely hear that I eat like a Mexican — one statement of many that reminds me that, in my Connecticut hometown, no one ever recognizes me as the Mexican I truly am.

To be fair to the approximately 80% white town I grew up in, the largest limiting factor to connecting to my Latino roots might actually be that my mom was the first one in generations to not be born in the Indian subcontinent (instead she was born in Ghana). This is to say that throughout my one year in Colombia, people often assume I'm Venezuelan or, with lesser frequency, Mexican. My favorite incident of mistaken identity was when an eight-year-old who I play soccer with walked by me with his parents and excitedly told them, “He’s from the United States.” His father proceeded to correct him by saying that I was Venezuelan. Once, while getting a ride to the outskirts of my town, the driver addressed me with, “Hey, you’re the Brazilian guy.” This greatly confused the four other passengers in the car and one woman corrected him with, “He’s the gringo (a word for American foreigners) people mistake as being Venezuelan.” Multiple taxi drivers have asked me whether I’m visiting family in Colombia; I’ve learned that, given the nearly two million Venezuelan migrants and refugees in the country, this isn’t an unreasonable question to ask a Venezuelan.

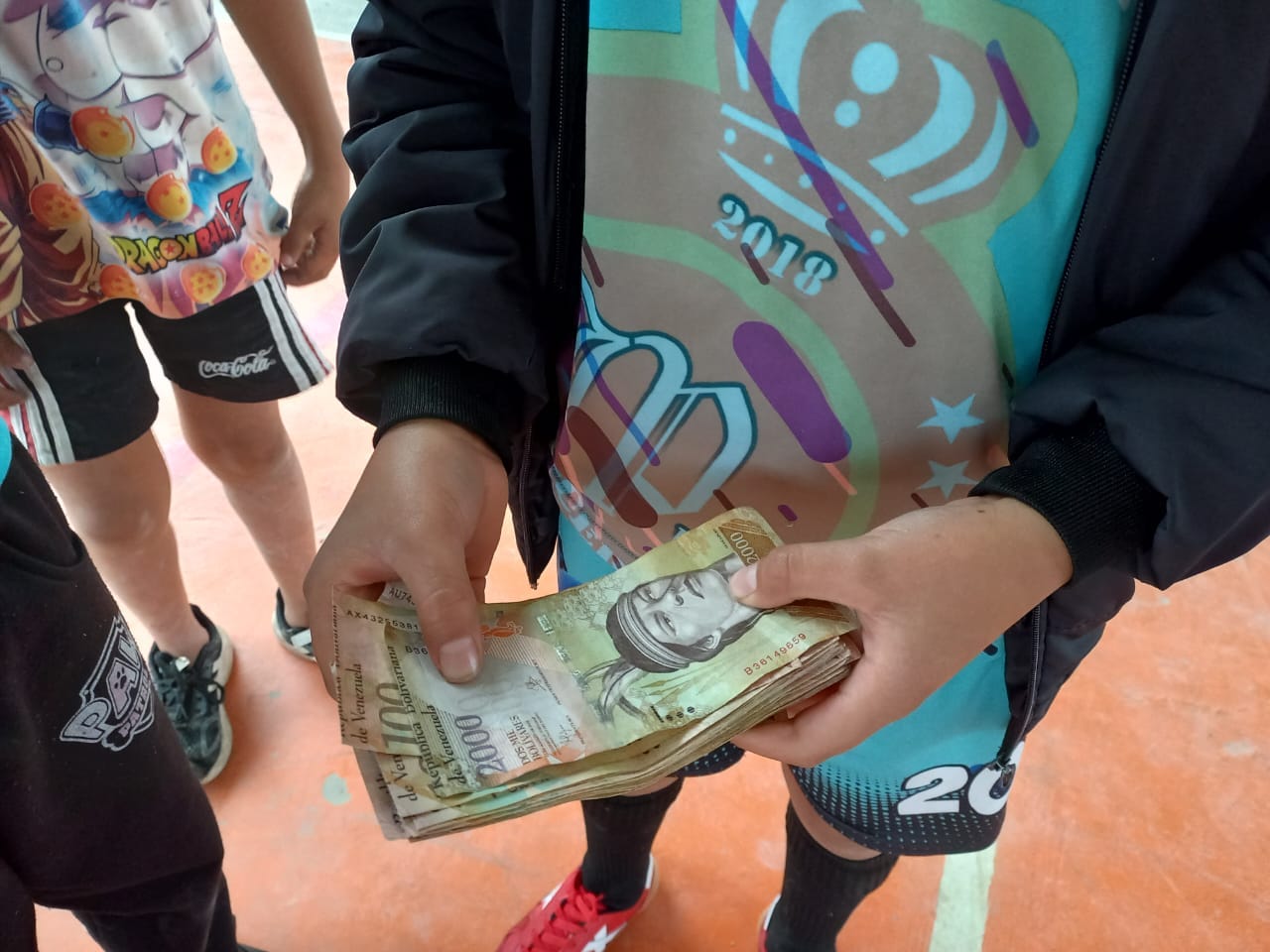

Often, people express to me their confusion about where I’m from. When I speak, they hear a heavy and bizarre accent that differs from the Venezuelan accent they're accustomed to. In my site — population: 10,000 — the Venezuelan accent is very prevalent. There are small neighborhoods dominated by Venezuelans and they have incorporated themselves into parts of the economy, owning or working at places such as restaurants, food stands, and barber shops. This integration angers some Colombians as they consider Venezuelans as job stealers, which is similar to the opinions some Americans have toward immigrants in the United States. As part of integration, I often play soccer with a group of Venezuelan kids. Due to the aforementioned stigmas Venezuelans face, Colombians voice disapproval of this activity. Many of these kids can’t remember Venezuela because they were born here or came here when they were really young.

These kids are subject to the derogatory term veneco. I occasionally hear this word thrown around at the school I’m assigned to work in as well as in the community. Over beers, an off-duty police officer from near Bogotá would explain to me that veneco is a slur to refer to Venezuelans who live in Colombia after he heard, to his amusement, I was routinely mistaken as being Venezuelan. Another person jokingly told me I should call some Venezuelans this word. Immediately, the police officer changed his light-hearted demeanor and sternly warned me not to do so.

Anti-Venezuela rhetoric in Colombia goes far beyond the perception that they steal Colombian employment. Despite Venezuela offering refuge for Colombians during various periods of turmoil, Venezuelan immigrants experience significant amounts of racism in Colombia. For example: Colombians routinely voice concerns about Venezuelans committing crime, though — similar to how some Americans imagine Mexican immigrants in the states perpetrate more crimes than American citizens despite data actually showing the opposite — they do nothing to increase crime rates. The head of security at the United States embassy in Colombia confirmed that while Venezuelans will, by default, be blamed for committing crimes, further investigation will sometimes conclude it was actually Colombians who committed the crime in question.

This belief has resulted in me interacting with Colombian police more than anyone else in my cohort in the form of random ID checks. In the nine months I’ve lived in the interior, I’ve been asked for identification six times. During the fifth check, I happened to be with LaTesha and her Colombian counterpart who was shocked at the number of times I had been stopped like this. The sixth check was the most intensive. At the Tunja terminal, three police officers and a K9 unit approached me and requested a pat down. Afterward, the officers and their dog proceeded to search my bags and examine my ID. Once they learned I was from the United States, the thoroughness of the search dropped dramatically. The demeanor of the officers took a sharp turn. Their mood lightened. Now excited and chummy, they greeted me with the standard question, “Que tal es Colombia?” The same thing happened with all of my previous ID checks.

While these ID checks and forced searches are annoying, I — unlike Venezuelans — have the luxury of playing the American card. I also have the support of a wonderful host family and their relatives. Prior to the police officers in my site getting to know me, they asked for my ID. When members outside of my immediate host family saw this, they immediately crossed two lanes of traffic to reach me and explain to the police officers who I was and where I lived. After the police officers left, my host family let me know the search likely happened because I was mistaken as being Venezuelan.

During these ID checks, I find myself resisting the urge to ask for a reason behind the search. Still, given a lack of understanding of my rights in Colombia and a fear of spiraling the situation, I always chicken out. I would not equate my experiences to minorities in New York City throughout the era of the Stop-and-frisk program. However, for actual Venezuelans, I would. For one, I can’t imagine that it’s good for Venezuelan-Colombian police relations. Further, there’s an argument to be made that the illegal detainments made during the two-decade long Stop-and-frisk program led to increases in crime committed by those who were searched. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy in which the act of treating people like criminals led to some of them acting like criminals.

Getting in touch with my Venezuelan-Mexican roots has thrown this socio-political problem into sharp contrast. Even though I have an easy way out, many of my countrymen do not. As an introvert, it can be tough for me to put myself out there. And as someone who is routinely mistaken as being Venezuelan or Mexican, I have a habit of blending in here as long as I don’t open my mouth or encounter police. These two factors are obvious challenges — the one upside being that my appearance means I get ripped off far less frequently than white PCVs. Still, some of the best people to pull me out of my introverted shell have been the incredibly welcoming Venezuelans in my town. I hope to return the favor soon as a PCV and fellow Venezuelan.

Las Diferentes Caras del Carnaval

Soledad Garcia-King, Turmequé, Boyacá, Colombia, CII-16

En el carnaval de Barranquilla se ven personas vestidas para representar la cultura indígena.

Esta pareja está vestida con un atuendo costeño. En la costa es común ver atuendos blancos con colores que resaltan. Son festivos y frescos para combinar con el clima de la costa.

Por todo el desfile se ven los sombreros tradicionales conocidos como los sombreros vueltiaos. Vienen de la cultura indígena Zenú. Están hechos con hojas de caña flecha, que es una planta nativa de la costa.

Para los espectadores siempre hay vendedores con comidas o bebidas. El desfile del carnaval suele durar 6 horas o más. Los vendedores proveen antojitos para que la gente esté cómoda mientras disfrutan de las carrozas.

Las marimondas son muy comunes en el desfile del Carnaval. Estos personajes empezaron como parte de un movimiento político, pero ahora se considera como el personaje ícono y cómico del desfile.

Algo que es muy aparente en el desfile del Carnaval es que se permite expresarse de una manera creativa. Las mujeres expresan su belleza con el maquillaje que usan, las prendas que adornan su pelo y su cuerpo. Es bonito saber que el desfile le da la libertad al ser humano de ser lo que quiera ser.

Chapter 1

Miles, Portland, ME, CII-16

Miles is a former Peace Corps trainee who lived in Palmar de Varela during Pre-Service Training and did not make it to service due to administrative policies.

Life here is different. The roosters scream in the morning, there is no need for an alarm. I meet LaTesha, Maida, Bobby and Soledad and we go for a run along a rough trail on the perimeter of the pueblo where we live. The gentle, flowing Magdalena River reflects a glint that we see so clearly it momentarily blinds our view of what we think are the glistening silhouettes of the Andean Mountains in the far horizon, but they could merely be clouds. As the sun starts rising, the brightness occludes these grand silhouettes, but the Magdalena now sparkles with a stronger glint that illuminates the fluorescent green vegetation that floats on top of the river. It is so ubiquitous that sometimes we can’t see where the wide river does and does not flow.

On the other side of the trail is a small, impoverished barrio full of beaten shanties built by Venezuelans looking to find a better life. The short sighted people tell us to stay away from them, but they are harmless to us. We run past a Venezuelan man smoking while defecating on the side of the trail near the brush. We feel uncomfortable, but not in danger. As we keep running, I hope to cross a team of storks indulging in their languid, early-morning solitude before taking flight, which Soledad and LaTesha gleefully pause and snap photos of. There are no storks today. Instead we hear a pack of barking hounds as we run past a finca. The sounds of their barks start to creep up on our backs. We can’t see, we pick up stones, the sounds are getting closer, we turn around and there is a pack of a dozen growling hounds chasing us. Maida loses her stride for a brief moment. She turns around, faces the hounds with direct eye contact, makes hand gestures to the snarling hounds that clearly indicate she is going to hurl a stone at them. They pause, turn their snarl into a weak whimper and anxiously retreat back to the finca that they came from in defeat.

We finished our four-mile run in less than half an hour and we are back in the center of our pueblo. Our efforts show because it looks like we went for a swim, fully clothed, instead of a casual morning run. I wrestle to take off the shirt that sticks to my body — humidity — as I walk by a tienda and exchange a few words with the owner who is still opening his store. I pay him a peso for a liter of water before chugging it down. The owner is also shirtless. By now the pueblo is fully awake, rushing motos dodge free-roaming mules and cattle on the street and raise dust that powders the leaves and mangos on the nearby trees. There’s a breeze that cools us down just a little. But the breeze carries a dust that sticks to our moist bodies just as it does the trees as we pass by on the way back to our host family’s homes.

Bobby exhales in disbelief and enthusiastically exclaims, “I can’t believe we are really in Colombia right now!” before we part ways.

Now, I’m alone with my thoughts as I finish the final stretch of my walk through the bustling street back to the house where I will shower and finish my morning routine. I acknowledge how the town we live in along the river with mountain silhouettes in the distance is very nice and I am very happy living a simple and unfamiliar life. I am very glad that I am beginning to make new friends. People are nice here, they show me a kindness and warmth that I couldn’t see before. The people have lived in this pueblo for their whole life and it is all they know. Every morning, my host mom sweeps her front patio of the dust that has been stirred up in the breeze by the honking motos from the night before. From the outside her house looks grand, the front has been freshly painted a white that reflects morning sunlight like snow that rests on the Colorado Rockies, my home from before. The inside of the house is bare: there is very little running water and furniture, the floors are dustier than the streets. My worries are starting to fall from my shoulders even though moisture and dust still cling to my skin. While the morning is clear, sunny, and home to vibrant birds chirping melodies from heaven to the rhythm of honking motos, I sense a heavy storm for the afternoon.

After I shower and eat breakfast, a white truck pulls up.

Let's be honest. None of us know why we are here. If you think you know why you are here then you don’t know why you are here and if you are looking to find something then you have trouble seeing and you will not find what you are looking for. The people who know what they want and tell you are liars. A person who knows what they want is content with where they are now. I thought I was looking for a new perspective, a new peace of mind, self expression and equanimity, but I did not fully know.

When the white truck showed up, I felt uncomfortable. My friend LaTesha even more so. It looked like it was ready to go to war, not pick up our cohort of humble pilgrims. It rolled through the middle of the pueblo, taking up too much space on our narrow roads, and children on bicycles stared at us in an awkward bewilderment. Ron and Lorenzo consider the local politics of a far away place. Some women talk about their long-distance relationships — a girl mentions her boyfriend’s salary as another strategizes how to keep her relationship alive. Victoria breaks out in a loud laugh from something LaTesha whispered to her. The fresh faces all had a discussion with the same topic: home, in the United States. What makes a home and why are we really here?

Staring out the window with my eyes wide open across the landscape where I don’t see anything, I come to realize that I am lost. I don’t know what is true or false. All I know is that I am a stranger in this foreign land with other strangers. The people who work in the tall tower in the city, a land of riches far from our pueblo, tell us they want the best for us. But I’m not sure they see either.

A Goodbye Letter

Bobby Richards Ciénega, Boyacá, Colombia CII-16

Dear GrandPedge,

You were a trailblazer, role model, world traveler, and countless more inspirations for countless people throughout your life. You were the senior care facility church carpool driver until you were 94. The self-designated resident botanist until 98. And the sole weekly movie-selection committee member until you moved out and in with my parents at 99. Most of all, you were Grandma to me and my siblings.