Vol. 2, Issue 1: OLD DOG / NEW TRICKS

In OÍSTE's first issue of 2024, Peace Corps Colombia volunteers share stories about unique challenges and adaptations.

A note from the editors: Please join us in wishing this iteration of OÍSTE a very happy first birthday! Our sweet winter storm has started to take their first steps and explore different finger foods and happily babble to strangers. Heartened by their healthy development, OÍSTE’s biological parents have decided to ditch it for grad school and other forays into the real world. That being said, please join us in welcoming our new executive board who dipped their toes in parenthood for the first time to carry this issue to the finish line. They’re hungry creatives who have a beautiful vision for OÍSTE’s future. The family grows! And what’s a toddler’s birthday without some hijinks? For the fourth issue of OÍSTE redux, volunteers share unique solutions to unique problems. Fun fact: this is the first issue in the history of OÍSTE redux that features submissions from all four active cohorts! This newsletter will cut off in your inbox, so be sure to click on the title to read it on-site in full! (P.S., Happy belated Birthday, Victoria!)

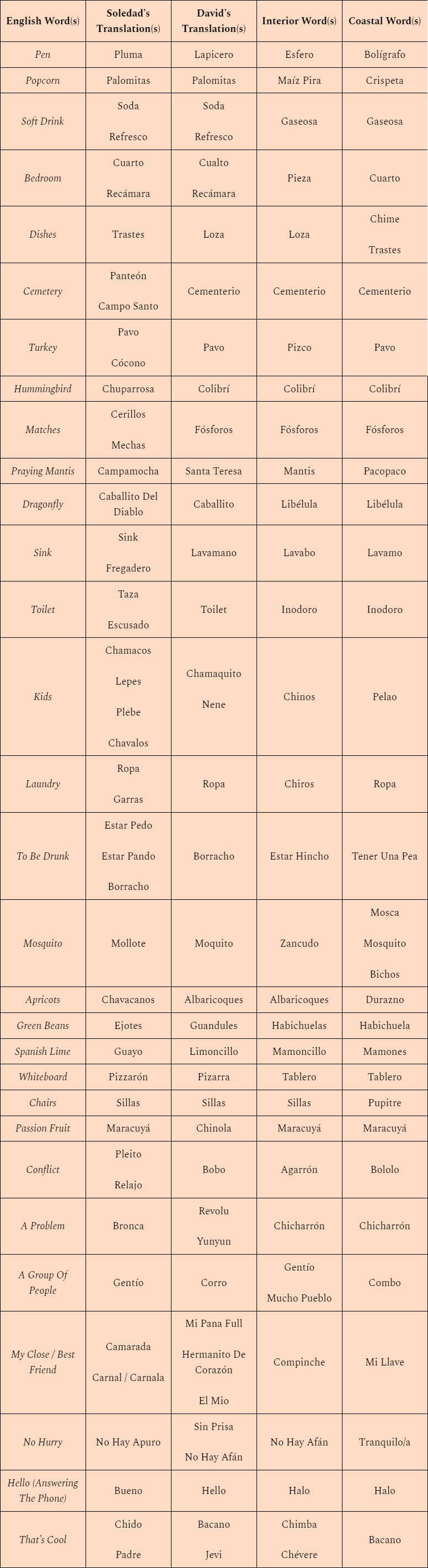

Just when you think you know Spanish, te das cuenta que no sabes nada

David Paulino and Soledad Garcia-King, Palmar de Varela, Atlántico and Turmequé, Boyacá, CII-16

When we signed up for the Peace Corps, we both felt pretty confident in our Spanish speaking skills. Both of us are native speakers. Both of us have been immersed in Latino culture since we were children. Little did we know, we were about to embark on a linguistic adventure where we would have to unlearn and relearn to integrate into our new surroundings. This article touches on just some of the linguistic surprises we have encountered and only begins to shed light on how the Spanish language can vary across the globe.

Hola, soy Soledad

Hola, soy Soledad. I am currently serving in the interior of Colombia. I was born in New Mexico. I am of Mexican descent. I grew up in an area where two distinct Spanish dialects are spoken. Because New Mexico is on the border, both New Mexican Spanish and Mexican Spanish can be heard in my home state. Spanish is my mother tongue, and I have spoken it all my life. I have always been fascinated with learning languages, so I studied Spanish in college and decided to teach it -- this year marks 20 years of teaching Spanish. I truly thought there was nothing more to learn until I arrived in Colombia.

Hola, soy David

Buenas, es David! I was born in New York City. Both of my parents were born in La República Dominicana. As a first-generation Dominican-York, I grew up learning Spanish and English at the same time. For a bit, I grew up alongside my cousins in The Heights, a neighborhood known for its large Dominican-American population. I even lived and studied in the Dominican Republic. Trust, I was confident in my Spanish coming to Colombia. Two days in and I was perdidooooo. I had to retrain my ear to be able to comprehend el Costeñol (Coastal Spanish), which is known for its speed, jargon, and idioms.

Below you will find a table to show the differences between the words we currently use and those we had to learn once we arrived in our respective regions.

En conclusión

Living on the coast has been nothing short of a blessing. This table demonstrates merely a fraction of the language’s diversity. It can be broken down even further based on regions or towns. Language is a magical thing, and through this experience I've learned to appreciate and fall in love with it. There were many times in our Pre-Service Training where we would discuss the similarities and differences between how I would say something, how Soledad would say it, and how our Language and Culture Facilitator would say it. This table was born out of those discussions and the fact that Soledad and I are now serving in two very different regions. It goes to show you that just when you think you know Spanish, no sabes nada.

On the Quest for Some Spice

Karina Gonzalez, Candelaria, Atlantico, Colombia, CII-17

One of the things that I initially missed while in Colombia was access to spice such as hot sauce, peppers, and so much more. The ají picante was good, but I was in desperate need of an extra kick to my food. Every summer, my dad would grow tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce, jalapeños. This sparked my journey to grow my own jalapeño plant. I anxiously waited for my seeds to arrive from home, thanks to my parents, so I could begin my attempt to plant and grow jalapeños on the Caribbean coast.

When I first planted my seeds in May, I was a new plant parent obsessively checking on their daily progress daily. I quickly became preoccupied with caring for my little seeds and made many mistakes. I was continuously worried about the dangers my plants faced, like the colony of ants that inevitably invade everything, the dogs at my house that destroy anything in their path, the thirteen curious toddlers that like to touch all they can when they come to my house, or the spontaneous and intense heat and rain of the coast.

By June and July, I was feeling relieved that I had managed not to kill my little jalapeño plants yet, and I was constantly finding them a nice spot in the sun and watering them consistently.

In August, I hit my first challenge: the rainy season was approaching. In prior months, my focus was entirely on ensuring my plants had enough water to survive the humidity and intense sun. Now, we were looking at more days of heavy rain days and not enough light. After a weekend away from my site, I found my plant drowning in inches of water! I scrambled to save it and found myself praying for a bright, hot, sunny day. After a few weeks of droopy leaves, I saw them begin to perk again and breathed a huge sigh of relief! I saw more and more flowers on the plant and knew that I just had to be patient. Come early October, I began to see the fruits of my labor (literally). By November, I had given the plants enough time to grow, mature, and ripen and could finally begin to enjoy spice again.

My first recipe was a simple, easy recipe my dad would make where you slice and pickle them in vinegar with some thinly sliced onions, garlic, salt, lime, and cilantro. I also started adding them to every meal and to my surprise … they were SPICY. They were so spicy that my lips and tongue tingled every time I ate. I realized I had a new challenge: gaining back my spice tolerance. After a year at site, I was reintroducing jalapeños to my diet, a level of spiciness that I had long left behind and could not handle anymore. I felt very proud of myself for being able to make and enjoy my dad's recipe. It reminded me of home and my dad pulling out the jar of pickled jalapeños with every meal during the summers.

This has been a learning process for me. Before this, I had never successfully grown anything nor had much of an interest in gardening. As I’ve found throughout my service, everything takes time to come together. I patiently waited for my jalapeños to grow and will now work on regaining my spice tolerance through an infinite amount of other jalapeños recipe ideas that I am excited to make. In the meantime, if you’re looking to add some heat to your meals, come find me on the Caribbean coast!

A Ranking of Catcalls

Page Victoria Robinson, Riohacha, La Guajira, Colombia, CII-18

For those who haven't met me in person, I am 5 foot 7 inches tall — above average for Colombians, specifically women. I’m incredibly pale despite my beach site, and, to top it all off, I am a natural redhead. I share this not to propose that I experience catcalling at a higher frequency than anyone else, but to point out the obvious: in Colombia, I stand out. I’ve lived abroad before so I’m used to not blending in. I’m also well aware that catcalling exists all over the world, especially in U.S. cities, but I find that Colombians have a special flair for the dramatic and I wanted to share a few of my favorites.

While we all know that ignoring catcalls is by far the best reaction, sometimes you hit a breaking point and just have to react. That being said, I’d also like to leave you all with a little recommendation my sitemate Kristen and I devised. We have found that when said with a smile and a friendly voice, we can get away with some quite creative comebacks in our native language.

“Flaca!”

“10/10 — Superlative: Weirdest Translation”

The Latin American custom to use physical attributes as nicknames will never cease to astound me. Born and raised in the U.S., it would be unthinkable to refer to someone based on their weight, height, skin color, or any other physical description. But here, gorda is a common term of endearment for your girlfriend and flaca is a perfectly acceptable thing to yell at a stranger in passing on your moto. This catcall seems flattering to an extent – it’s certainly a nice break from the other overtly sexual jeers readily available. But I find I best understand the strangeness of it when I translate it to English and try to imagine yelling “skinny!” out my car window. I don’t welcome any stranger’s assessment of my physical appearance but I suppose that in the grand ranking, this one gets a pass. Truth be told I’d much rather they yell “fuerte” or “musculosa” as I’m exiting the gym. Honestly guys, it’s been months; a little acknowledgment of my hard work would be nice.

Suggested Response: Your hairline is receding.

“Barbie!”

“7/10 — Superlative: Most Problematic”

The Barbie movie was a landmark moment in feminist history, and I urge anyone who has not seen it to do so. However, in the pueblos it has made being tall and white an all-time big deal. Now don’t get me wrong, an eight-year-old Page would have died to be compared to Barbie. As far as compliments go, this one is pretty high praise. However, I tend to rank this comment right next to “blanca!” — another common catcall I receive. Living in a town where my whiteness makes me stand out, I can’t help but feel that any comments made about my beauty are steeped in a history of colorism. Do you think I’m beautiful because I’m pretty or because I’m white? I, unlike many of my peers, grew up with the privilege of existing primarily ignorant of my skin color. My whiteness never drew unwanted attention from police, teachers, storekeepers, etc. I know it likely benefited me in more ways than I will ever be aware of. In the U.S., I was often encouraged to get a spray tan to make myself more attractive. Here I’m urged to stay out of the sun lest I get darker. So while Barbie seems like a compliment, in actuality it is steeped in a fetisism of difference.

Suggested Response: I’m taller than you.

“Hermosa” *gasp of surprise* “Blanca!”

6/10 — Superlative: Funniest

This moment will always hold a place of endearment for me as it was neither threatening nor creepy but rather quite funny. (We love a man who finds his humoristic catcalling sweet spot!) I most often get catcalled by men in passing, whether from cars, motorcycles, or bikes. This is a point of interest for me as it makes me question the purpose of the catcall in the first place. What is a man’s intention when he yells out “guapa” as he speeds past me on his motorcycle? He clearly has no plans of stopping and asking for my number and he must know he’ll never see me again. He also rarely slows enough to hear my response. What if I also found him guapo? Any chance of a meet-cute is ruined when he speeds off into the sunset. Really, I say this in this jest: the man who pulls over and tries to ask for your number is a whole different level of creepy, but the man who catcalls you with no follow through or follow up — what is his goal? The man who made this particular remark happened to be on a bicycle. He first yelled out “hermosa!” when approaching from behind — terrifying. He then continued on his merry way but happened to look back as he passed and, with obvious surprise, realized I was also a foreigner. “Blanca!” he gasped, more of a knee-jerk reaction than a catcall. I couldn’t help but glance down at myself and gasp along with him as if I too had just realized my skin color, which if we were both being honest at that moment in the midday sun was clearly more “rosa!”

Suggested Response: I teach your grandchildren.

*Pssst psst psst* (imagine the sound you’d make to call a cat)

2/10 — Superlative: Most Demeaning

This one takes catcalling to a whole new level. I can honestly say that before arriving in Colombia I never understood the feline factor of catcalling. But after repeatedly being summoned like a stray cat, I must say it’s a rather fitting term. The first few times I heard it I genuinely thought someone must have lost their cat. After a couple weeks, I did the math and surmised that there couldn’t possibly be that many missing cats in Colombia. I’ll be the first to announce that I have no patience for being summoned like an animal, so this one ranks as my all-time least favorite. However, I also find it one of the easiest calls to ignore as I remind myself that no self-respecting person would ever try to hail another person like an animal. I like to believe that these men truly are looking for their lost furry friends, and I wish them all the best in finding both their cats and manners.

Suggested Reading: I’d rather be shot/eat garbage/chew glass.

All in all, my biggest critique of catcalling (apart from its generally degrading nature and inherent threat of violence) is its lack of originality. Just once I’d love someone to exercise a little creative freedom and hit me with something truly awe-inspiring. That being said, there were many long-winded cat calls that didn’t make this list. (One honorable mention goes to yet another gentleman on a bicycle who rode by while professing his love for me and my friend, recounting that he’d always wanted to be with a gringa and proposing marriage to us both, never breaking eye contact as he steadily cycled away.)

In most instances it’s a mere annoyance, unwanted attention when I’m simply trying to get from point A to point B. At times, there’s an edge of flattery — occasionally being called pretty isn’t that bad. Sometimes it's outright outrageous. I’ve been called hermosa looking my absolute worst more times than I can count. Like come on gentlemen, we’ve just met, don’t start lying to my face already! But more often than not, being verbally harassed is terrifying.

We’re taught to smile and keep moving. However, on multiple occasions men have pulled over in cars or motorcycles and continued to try and get my attention even after I’ve ignored their advances. Every time a man calls out to me on the street I know that there is a very real chance he could react badly to being ignored or rejected and become physical. It is exhausting to be a woman at times. The moment I step out of my house, I know that every minute I’m on the streets I am going to be barraged by an onslaught of verbal harassment. It doesn’t matter what I’m wearing, who I’m with, where I’m going or what time I’m out. For the simple fact that I am a woman and a foreigner, I can expect to be catcalled endlessly.

So I write this piece to share a little humor but also I hope in solidarity with anyone, regardless of gender, who feels the constant weight of standing out and needs a little laugh. I want to make it very clear that while I make light of the situation here, it is by no means to diminish the very real fear that accompanies being constantly harassed simply for existing.

New Beginnings

Soledad Garcia-King, Turmequé, Boyacá, CII-16

¡En Barranquilla Me Quedo!

Ashani Sharma, Tabio, Cundinamarca, CII-19

A security incident a few days into service immediately threw a wrench in my Peace Corps plans. No more spending nights chatting and getting to know host family members. No more building relationships with my counterparts and getting ready for the new school year. No more running into students on the street and integrating into my community.

I was on the fast track to a site change with a stop in Barranquilla and little to no idea of how long I would be there. I’m grateful for the time I was able to spend with volunteers passing in and out of Casa Colonial, and to Peace Corps for allowing a volunteer to stay with me for a week as support (shout out Nico!). But I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t a difficult time, fraught with loneliness and stress. It didn’t help that I couldn’t find much to do in Barranquilla aside from going to the mall, an activity which I have found odious for years.

But I made the best with what I had.

Alongside several nights alone in my hotel room, there were many phone calls to friends back home, and there was even more Mexican food– that too of the spicy variety, which can be hard to come by in Colombia. With the help of a certain David Paulino, I discovered perhaps the best Mexican food in the city and certainly the best vegetarian food I’ve had in Colombia. I ate the berenjena burrito from Guadalupe de Reyes with three differently spiced salsas every day for 24 days straight, always accompanied by a jugo de mango en leche on the side, or as I liked to call it, mango lassi. Now that I’ve survived to tell the tale, I can confidently say that I loved every single bite, slurp, and burp.

The employees at Guadalupe de Reyes quickly became a source of friendship and support for me during an otherwise isolating time. I looked forward to walking in every day and seeing Mayelis, Henry, and Ruth awkwardly smiling, almost as if to say, “Damn, this girl’s in here … again?”

That’s how it started at least, but soon enough those shy smiles turned into hearty laughs and Henry swiftly getting to work on the berenjena and burrito components of my visit. I got to know the ins and outs of my new friends’ lives and was able to open up about my reasons for being in Barranquilla. It was easily the best part of my days in limbo.

Spending a prolonged period of time in Barranquilla also allowed me to spend the holidays with my host family from training in Palmar de Varela, whom I love more than anything (more even than Ms. Berenjena — hard to believe, I know). Christmas Eve in Palmar was magical. The sun was going down, the vallenato was vallenato-ing, and I was about to partake in the first Christmas celebrations of my life.

I made my rounds to all the señoras of calle cuatro, who had been waiting for me to visit for weeks. I came bearing pan dulce, and we all relaxed and caught up on their patios in the harsh coastal heat, which I am now glad to have forgotten. Sra. Marí and I ran into each other’s arms, and I learned all about how Sr. David’s tenacious, unrequited interest in her 50 years ago transformed into the lasting love I now know.

After my chat with the señoras, I accompanied my host mom and grandmother to a special Christmas mass at church. When it was time for la paz, the old woman sitting next to me gave me a blessing and said a prayer for my protection and health. I cried.

I was so moved by her kindness and love for a stranger, and thinking about the incident that brought me to Barranquilla to begin with only made me more emotional.

The deep serenity and calm of church quickly faded, and within an hour I was downing shots of rum and aguardiente with my family, dancing with my host sisters, and completing a Disney princess puzzle with the little girls down the block. Just as the clock struck midnight, dinner was served, and I broke my vegetarianism of two years to try my family’s special Christmas chicken dish. I swore everyone to secrecy, lest the señoras find out and get the wrong idea; it was just a one time thing, chicas.

We all filed into the same room after dinner to go to bed, slumber party style, and my host mom handed out little juguetes to my host siblings and me as gifts. I was graced with the much-envied “water game,” a little orange water ring-toss toy, which resembles either a happy meal prize or a Blackberry circa 2008.

Christmas Day commenced with my 15-year-old host brother mixing his juice with his finger at the breakfast table, my host mom exasperatedly requesting that he stop, him continuing, and everyone bursting into laughter. It was moments like these where I really felt like I was part of the family.

We spent the rest of the day dancing at the discoteca, and I felt so grateful to be surrounded by such genuine and caring people, to have the privilege to call them my family.

I returned to Barranquilla the next day.

Now, in a little Andean mountain town frequented by rolos and extraterrestrials alike — Tabio, Cundinamarca — I contemplate Oíste’s new theme, “wild card.” I’ve lived in volunteer couple John and Isabelle’s apartment here for a week and a half now, and creeping into the new year, still without a site, I can’t help but feel that my entire time in Colombia has been a “wild card” of sorts.

Ultimately, though I did quedarme in Barranquilla for far longer than I would have anticipated or even liked, my time there lent itself to finding new friends and spending precious time with old ones– not to mention the berenjena in the middle of it all. Now as I look forward to finally moving to my new permanent site in the Andes in a few days, I almost miss Barranquilla.

Luckily, it’s only ever just a song away.

The Republican Museum

Lorenzo Boni Beadle, Cucaita, Boyacá, CII-16

A refrain I’ve commonly heard speaks to the social and cultural disunity of the politically centralized Republic: “There is not one Colombia, but thousands.” Identity is regional (cachacos versus costeños), departmental (paisa), municipal, linguistic, racial, indigenous or pseudo-indigenous — each its own republic of normative codes. The Republic has an anthem. Every department, municipality, and colegio has an anthem. SENA — the equivalent of the Small Business Administration — has its own anthem. Tension over which agents ought to have a monopoly on setting the tenor of identity is an international commonality. So too are the technologies employed by these actors to produce and reproduce identity. One such technology is the museum. In Colombia, museums play different roles with respect to national identity: some —republican museums — help to establish and exhibit its contours in the heart of the capital, others — collaborationist museums — support this effort by tying the legacies of their host communities to national narratives, and still others — partisan museums — speak about identity and history in a way contrary or unrelated to a broader Colombian nationhood at all.

Republican Museums

What I call the republican museums are those located in Bogotá and under the jurisdiction of the Ministerio de las Culturas, las Artes y los Saberes or, unusually, Banco de la República. These are the museums at the forefront of presenting Colombia as a united republic. They propose and determine a canon that reflects an internationally-legible colombianidad. Foremost among them is el Museo Nacional de Colombia which has a wonderful permanent exhibit dedicated to the museum’s own history. Just outside, you can learn about the Penitenciaría Central de Cundinamarca — otherwise known as el panóptico — which once existed on the periphery of Bogotá but was gradually absorbed as the capital grew, and has now become the site of el Museo Nacional.1

The pre-history of el Museo Nacional begins with the diplomatic missions of Francisco Antonio Zea between 1820 and 1822. Zea sought European expertise to map Colombian territory, categorize and inventory Colombian natural resources, and devise athe means of exploiting both to the end of material progress. By liaising with European counterparts, he introduced Gran Colombia as a member of the international scientific community.2 With the resources provided, Zea founded a chemistry lab, a physics office, a minerals collection, and a library. Though Zea died in 1822, the next year would see the passage of a law establishing el Museo Nacional.On July 4th, 1824 it officially opened. An early Museo primarily concerned itself with natural history and significantly contributed to then-emerging paleontological discourse.

Within a decade, the Museo began to move away from its scientific-industrial role. When Joaquín Acosta’s directorship began in 1832, the Museo started to focus on reinforcing principles of national identity. This introduced exhibits that would reflect the national character of what was now la República de la Nueva Granada and situate it within the universal history of nations.3 The Republic would be a state with its own particular historical narrative: “cosmopolitan and oriented toward material progress.”4 Acosta, like Zea, was inspired by European practices and had drawn inspiration from museums in France, Switzerland, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

As the Museo’s investigative function dwindled into irrelevance and the state was wracked with instability, its profile as a demonstration of and justification for national unity grew in scope. Both Liberal and Conservative elites held vague, modernist ideals like civilization and progress in common, which were reflected in the Museo’s increasing focus on exhibits that augmented the state’s national profile. While by 1850 it had lost institutional autonomy (placed under the Biblioteca Nacional) and many of its subsidiary elements had been parceled away to other organizations, a refounding in 1881 established the Museo’s new mandate: “to exhibit samples of national wealth and products, highlight historical memories of the country and stimulate the advancement of natural science.”5 The refounding focused the Museo, re-centralized its most important assets, and definitively directed it toward the task of nation-building.

Over the 20th century, the Museo’s nation-building focus shifted to culture, heritage, and conservation: priorities that persisted across political sea-changes and even military governments. Of course, the nature of national heritage is and was contested, but these were frameworks the Museo employed to pursue the broad program of “acculturating the masses.” In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, institutional condescension had given way to values like inclusion and multiculturalism. The Museo remains constituted along Euro-American lines and has continued to play an active role in the reflection and reproduction of national values.

Ostensibly, the republican museum should operate as a consensus-building mechanism, neutral with respect to the political features of that consensus. However, merely by posing mediums in which the nation is presented, el Museo Nacional is actively participating in the content of colombianidad. Local traditions that are difficult to capture, contextualize, and explain will be sidelined whereas participatory features of culture like dance can be captured as images or videos, but not quite experienced on their own terms.

El Museo Nacional is not an evil institution. Especially since the more liberal 1991 constitution incorporated the concerns of much broader swathes of society than its 1886 antecedent, it has become more inclusive and more reflective with respect to its own role in Colombian nationhood. However, as a republican museum, it is important for visitors to be conscious that el Museo Nacional is and has always been focused on the cultivation of a Colombian canon. Due to the twin constraints of international museological standards and nationalist profile, the Museo will never present a complete Colombia. It is bound by the physical and normative features of museum exhibitions and the need to propose and reinforce a united, centralized Colombia. Even with an exhibit fully devoted to the history of the Museo’s role in defining the nation, it is not a tendency that can be avoided. To do so would be to concede that the premise of a national museum may be flawed.

Collaborationist and Partisan Museums

The museums outside of Bogotá take on largely different social roles to their republican counterparts. I have placed them into two broad categories: collaborationists and partisans. The collaborationist museum endeavors to build a local profile that can be firmly associated with the national story told by republican museums. The partisan museum is a rogue museum that dispenses with any concrete relation to national narrative in favor of localism and particularity. Partisan museums do not present profiles that can be easily co-opted by museum nationalism.

Villa de Leyva features both varieties. As a historical town that has been pining for UNESCO World Heritage Site status, Villa de Leyva’s museums often present the way that the town has contributed to the Republic’s character and development. Perhaps the premier collaborationist museum in this vein is the Casa Museo Antonio Nariño. Nariño was one of the titans of the early republic, and much of the Casa Museo — occupying Nariño’s former home — is dedicated to biographical details. However, some portions of the Casa Museo are explicitly focused on situating Nariño’s contributions in a universal historical narrative and its exhibits detail his translation of the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,” thereby positioning him and the early republic in a global history of revolution, democracy, and human rights. By placing Nariño in dialogue with these events, Villa de Leyva locates itself as the city where it all happened. Strictly speaking, this isn’t incorrect. Nevertheless, it extends republican museumhood over Villa de Leyva by treating it as a kind of wellspring where the founding fathers laid down the intellectual foundations of the Republic. The collaborationism of the Casa Museo stems from its effort to proselytize about the national history in a manner that is so instrumental to the construction of a republican identity.

Just outside of Villa de Leyva lies a rival of the republican museum: el Museo Comunitario El Fósil. El Museo Comunitario is not owned or managed by the central government, the department of Boyacá, the municipality of Villa de Leyva, nor any of its veredas. It is run entirely by an unaffiliated community association. Were it not, it would likely see its exhibits — including a full-sized kronosaurus skeleton — swiftly relocated to Bogotá. A tour of el Museo Comunitario begins with the story of the discovery by a local campesino, the excavation undertaken by the landowner and a father-son geologist team, and the community leader who relentlessly defended the fossil. The exhibits include the famous kronosaurus, but also a great number of other fossils including dinosaur eggs and ammonites. What makes el Museo Comunitario partisan is the initial introduction: these exhibits are not contextualized as part of a national history. They are understood purely on local political terms. This is what makes el Museo Comunitario a partisan museum: it has remarkably little interest in participating in the national story. The focus is entirely on the fossils and those who discovered and defended them. The exhibits and findings exist to the end of a more neutral scientific inquiry, the sort of thing that causes children to become initially interested in dinosaurs.

As with republican museums, collaborationist museums are not evil, nor are partisan museums good. Both reflect the political priorities of museum founders and directors. While I find this framework particular to Colombian museology in that it can’t easily generalize, I do believe it a useful aid for people visiting Colombian museums, specifically to consider the role that these spaces play in Colombian social and cultural life. The exhibitions of art and ‘ologies should be understood as doing something beyond neutrally presenting themselves for visitor consumption.

When I tour friends around Greater Boston, we visit the Institute of Contemporary Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Though there are many other options, these are the ones I gravitate toward. These museums have always played an apparent and straightforward role to me; I’ve never situated them as social machinery contributing to citizen identity or municipal profile. In Colombia, these functions are a lot more obvious. The ICA locates the city as one of the participants in the modern art discourse. Every ‘great city’ likewise must have an MFA or some institution dedicated to fine arts and universal history. These functions should be elaborated upon to understand the image Boston presents to its urban peers, but I suppose I’ve just spent more purposeful time in Colombian museums than I have in those of the city where I was born.

A prison whose construction started in 1874 and, despite its nickname, didn’t end up functioning as or much resembling a panopticon.

First ancestor of the Republic of Colombia, composed of modern-day Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Ecuador, and parts of Peru and Guyana.

Second ancestor of the Republic of Colombia, composed of modern-day Colombia, Panama, and the territories of some surrounding states.

“La historia del museo y el museo en la historia,” Museo Nacional de Colombia

Ibid.