B is for Bachué

Does the origin of the legends we tell really matter? Or maybe just the fact that we believe them is enough?

According to local legend, all Muiscas originated from Bachué, The Goddess of Fertility. In what is now the department of Boyacá, Colombia, she emerged from the waters of Lake Iguaque holding a 3-year-old boy by the hand. That male child grew up to become Bachué's husband. Together, they populated the land before transforming into snakes and returning to the same sacred waters from whence they came.

At least, that was the story told by Pedro Simón, a Spanish franciscan friar who chronicled indigenous life and legends from this part of South America in Noticias Historiales de las conquistas de Tierra Firme en las Indias Occidentales. (Translation: Historical news of the conquests of the mainland in the West Indies)

While he has been hailed as one of the most important Muisca scholars, one can't help but wonder if he can be considered a reliable narrator. After all, the conquistadors he accompanied to Cartagena de Indias in 1603 continued the rampage of previous Spanish invaders who slaughtered and spread deadly diseases to nearly every indigenous person they encountered as they massacred their way from Santa Marta through Muisca territory while destroying virtually all physical evidence of their culture.

The Spanish colonizers who followed in the conquistadors' footsteps enacted laws prohibiting any written record of all things indigenous, in a mostly successful effort to annihilate any memories that survived. And while several other chroniclers, such as Juan Fodríguez Freyle, Juan de Castellanos, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, and Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita recount stories with similar themes and details to Simón's, their reports may be similarly tainted, for the same reasons.

So, who is to say whether — and how much of — the legend of Bachué is authentic? Did the Spaniards accurately report stories they claimed to have learned, first-hand, from the indigenous people they encountered? Could they fully understand and convey the stories they may have heard, considering the language and cultural barriers that surely existed between Spanish-speaking invaders and the Chibcha-speaking residents?

These are some of the questions that engage Julián Leonardo Garavito Rincón, Professor of Indigenous Architecture at UPTC (Colombian University of Pedagogy and Technology), located in Tunja, the capital city of the central Andean region of Boyacá

"All the stories we have come from the Spaniards, who massacred the Muisca," he says. "Maybe they filled gaps in understanding with made-up deities based on mythical gods they already knew about, from Greek and Roman mythology and from the Incan conquest. Maybe they fabricated the incestuous legend of Bachué to undermine indigenous culture and lift up their own. We can't know for certain where these legends originated."

Without a doubt, those true and/or tainted legends abound. Besides Bachué, key Muisca deities include

Sué, the sun god. He was worshiped on the summer solstice by nobles seeking blessings for the annual harvest.

Chía, the moon goddess and wife of Sué. Worshippers offered ceramics and gold to her during ceremonies organized by priests in her honor.

Bochicha, the messenger god of civilization, who supposedly arrived from the vaguely described "East." He appeared as an old man with a long, white beard, much like the Incan god Viracocha, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, and several other Central and South American deities.

In regards to Bochica and Quetzalcoatl, this excerpt from a machine-translated Wikipedia entry helps illustrate the "how true is it, really?" concept:

Not one cultural representation of either of these gods, painted, sculpted, et cetera, show them bearded in any sense the Spanish colonizers believed they would have been.[citation needed] There is no evidence in the abundance of Mesoamerican art of European influence, most stridently ruled out by the likenesses they gave themselves and their gods.[citation needed]

There have been questions[according to whom?] on the authenticity of the preserved stories, and to what level they have been corrupted by the beliefs and imagery incorporated by Spanish Christian missionaries and monks who first chronicled the native legends.[4][vague]

Archaeological evidence (or the lack thereof) aside, Muisca culture and legends are venerated throughout the department of Boyacá. Artistic depictions of Muisca culture and characteristics are displayed prominently, in the form of paintings and statues.

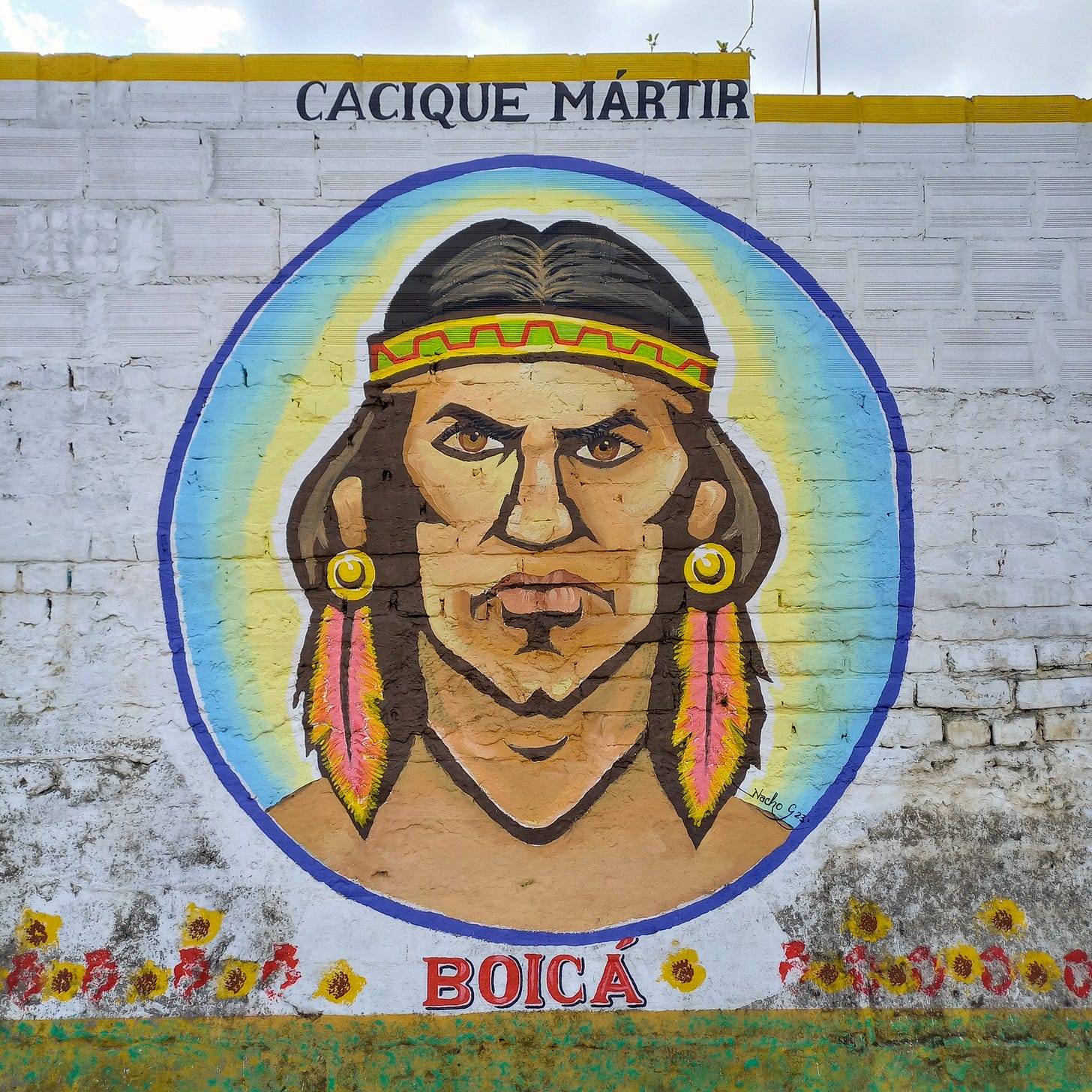

Visitors to Boyacá, Boyacá are welcomed by a larger-than-life portrait of a bare-chested Muisca warrior. Cacique Mártir - Boicá (the "martyred chief of Boyacá") sports a woven headband and gold earrings adorned with large feathers. His prominent brow, wide nose and sculpted jawline evoke a certain American football team's former mascot and logo.

However, according to Julian, "We don't know how they dressed, whether for daily wear, or festival wear."

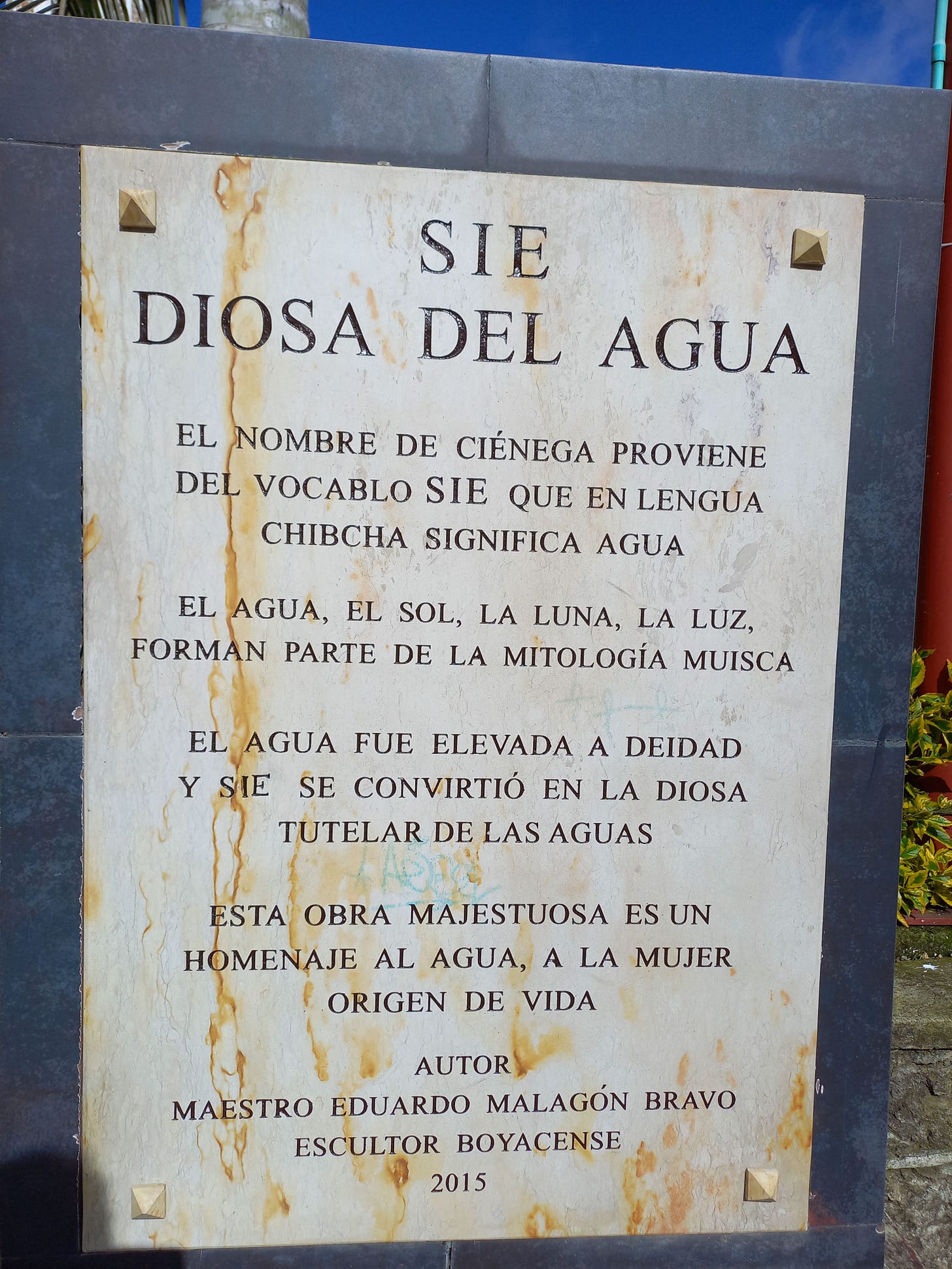

Plaque translation: The name of Ciénega comes from the word Sie, which in the Chibcha language means water. Water was elevated to a deity and 'Sie' became the tutelary goddess of the waters. This majestic work is a tribute to water, to the woman who is the origin of life.

Just a few miles away, in my tiny pueblo of Ciénega, a startlingly perky statue of a topless Sie, the Muisca water goddess, nearly steals the spotlight from the community's majestic, domed, Gothic cathedral.

Despite the adamant insistence of Ciéneganos, young and old, who say the statue depicts a well-documented deity from the local indigenous culture, I have so far found no mention of a Muisca water goddess named Sie outside of my pueblo. However, I have come across scholarly articles confirming that sie is, indeed, the chibcha word for water.

Julian explained that, while many legends are not supported by historical evidence, they are no less sacred to the people who believe them. "People want to remember, because without memory, there is no identity," he says. "When your entire history has been destroyed, you want to create stories and rituals of your own to hand down to your children, even if it is a personal interpretation."

Those stories may prove to be a key tactic in the ongoing neo-Muisca movement in Colombia. Activists are struggling to reclaim and recreate a heritage in the wake of destruction left behind by the conquerors. At the same time, they are fighting for official recognition from the national government. But this requires evidence of a language that was rather effectively annihilated by conquistadors and colonizers.

So, in the absence of physical evidence, legends both endure and arise, in a cycle of resilience that keeps cultures alive, by hook or by crook.

As far as Julian is concerned, there is sufficient space in that evidentiary vacuum for a neo-Muisca goddess like Sie to rub shoulders with the legendary Bachué.

Disclaimer: The content of this publication is generated by individual volunteers. The opinions and thoughts expressed here do not reflect any position of the United States government or the Peace Corps.